Airport Traffic Patterns

Airport Traffic Patterns

To assure that air traffic flows into and out of an airport

in an orderly manner, an airport traffic pattern is established appropriate

to the local conditions, including the direction and placement of the pattern,

the altitude at which it is to be flown, and the procedures for entering

and leaving the pattern. Unless the airport displays approved visual markings

indicating that turns should be made to the right, the pilot should make

all turns in the pattern to the left.

When operating at an airport with a control tower, the

pilot receives, by radio, a clearance to approach or depart as well as

pertinent information about the traffic pattern. If there is no control

tower, it is the pilot's responsibility to determine the direction of the

traffic pattern, to comply with the appropriate traffic rules, and to display

common courtesy toward other pilots operating in the area.

The pilot is not expected to have intimate knowledge of

all traffic patterns at all airports, but if familiar with the basic rectangular

pattern, it will be easy to make proper approaches and departures from

most airports, regardless of whether they have control towers. At tower

controlled airports, the tower operator may instruct pilots to enter the

traffic pattern at any point or to make a straight-in approach without

flying the usual rectangular pattern. Many other deviations are possible

if the tower operator and the pilot work together in an effort to keep

traffic moving smoothly. It must be recognized that jets or large, heavy

aircraft will frequently be flying wider and/or higher patterns than lighter

aircraft and in many cases will make a straight-in approach for landing.

Compliance with the basic rectangular traffic pattern reduces

the possibility of conflicts at airports where air traffic is not being

controlled by an FAA control tower. While accident statistics for each

year show an improvement over previous years, it is known that the majority

of midair collisions occur in the vicinity of nontower airports, under

visual flight rules (VFR) weather conditions. It is imperative then, that

the pilot form the habit of exercising constant vigilance in the vicinity

of airports even though the air traffic appears to be light.

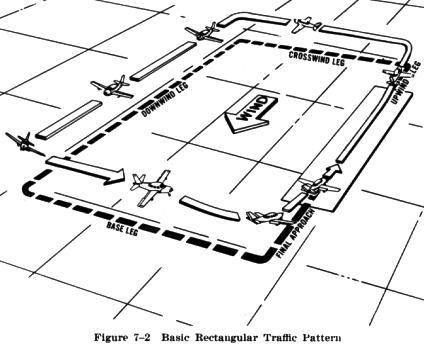

| The basic rectangular traffic pattern is illustrated in

Fig. 7-2. The traffic pattern altitude is usually 1,000 feet above the

elevation of the airport surface. The use of a common altitude at a given

airport is the key factor in minimizing the risk of collisions at nontower

airports. At all airports, the direction of traffic flow (in accordance

with FAR Part 91) is always to the left, unless right turns are indicated

by approved light signals or visual markings on the airport, or the control

tower specifically directs otherwise.

It is recommended that while operating in the traffic pattern

at nontower airports the pilot maintain an airspeed that conforms with

the limits established by FAR 91 for tower controlled airports: no more

than 156 knots (180 MPH) for reciprocating engine |

|

aircraft or 200 knots (230 MPH) for turbine powered airplanes. In any case,

the speed should be adjusted, when practicable, so that it is compatible

with the speed of other aircraft in the pattern.

The basic rectangular traffic pattern consists of four

"legs" positioned in relation to the runway in use. In the following discussion,

reference is made to a "90 degree turn" from one leg to the other since

the ground track of each leg is perpendicular to the preceding one. The

actual change in the airplane's heading during those turns will be more

or less than 90 degrees depending on the amount of correction necessary

to counteract wind drift.

The upwind leg of the rectangular pattern is a straight

course aligned with, and leading from, the takeoff runway. This leg begins

at the point the airplane leaves the ground and continues until the 90

degree turn onto the crosswind leg is started.

On the upwind leg after takeoff, the pilot should continue

climbing straight ahead until reaching a point beyond the departure end

of the runway and within 300 feet of traffic pattern altitude. If leaving

the pattern, the pilot should continue straight ahead, or depart by making

a 45 degree left turn (right turn for a right-hand pattern).

The crosswind leg is the part of the rectangular pattern

that is horizontally perpendicular to the extended centerline of the takeoff

runway and is entered by making a 90 degree turn from the upwind leg. On

the crosswind leg the airplane proceeds to the downwind leg position.

Since in most cases the takeoff is made into the wind,

the wind now will be approximately perpendicular to the airplane's flightpath.

As a result, the airplane will have to be crabbed or headed slightly into

the wind while on the cross wind leg to maintain a ground track that is

perpendicular to the runway centerline extension. This factor will be further

explained in a later chapter covering wind drift and maneuvering by reference

to ground objects.

After reaching the prescribed altitude for the traffic

pattern and when in the proper position to enter the downwind leg, a level

medium bank 90 degree turn should be made into the downwind leg.

The downwind leg is a course flown parallel to the landing

runway, but in a direction opposite to the intended landing direction.

This leg should be approximately 1/2 to 1 mile out from the landing runway,

and at the specified traffic pattern altitude. During this leg, the prelanding

check should be completed and the landing gear extended if retractable.

The downwind leg continues past a point abeam of the approach end of the

runway to where a medium bank 90 degree turn is made onto the base leg.

The base leg is the transitional part of the traffic pattern

between the downwind leg and the final approach leg. Depending on the wind

condition, it is established at a sufficient distance from the approach

end of the landing runway to permit a gradual descent to the intended touchdown

point. The ground track of the airplane while on the base leg should be

perpendicular to the extended centerline of the landing runway, although

the longitudinal axis of the airplane may not be aligned with the ground

track when it is necessary to crab into the wind to counteract drift. (This

will be discussed in the chapter on Landing Approaches and Landings.) While

on the base leg the pilot must ensure, before turning onto the final approach,

that there is no danger of colliding with another aircraft that may be

already on the final approach.

As stipulated in Federal Aviation Regulations, aircraft

while on final approach to land, or while landing, have the right of way

over other aircraft in flight or operating on the surface. When two or

more aircraft are approaching an airport for the purpose of landing, the

aircraft at the lower altitude has the right of way, but it shall not take

advantage of this rule to cut in front of another which is on final approach

to land, or to overtake that aircraft.

The final approach leg is a descending flightpath starting

from the completion of the base to final turn and extending to the point

of touchdown. This is probably the most important leg of the entire pattern,

for here the pilot's judgment and technique must be keenest to accurately

control the airspeed and decent angle while approaching the intended touchdown

point. The various aspects are thoroughly explained in the chapter on Landing

Approaches and Landings.

|

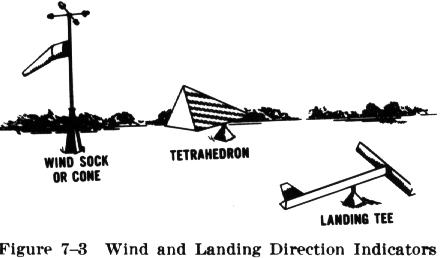

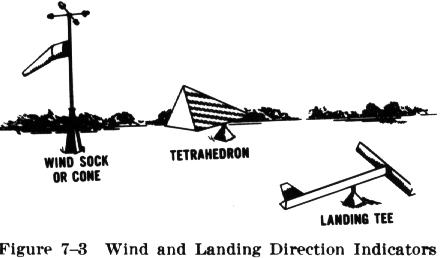

To enter the traffic pattern at an airport without a control

tower, inbound pilots are expected to observe other aircraft already in

the pattern and to conform to the traffic pattern in use. If no other aircraft

are in the pattern, then traffic indicators on the ground and wind indicators

must be checked to determine which runway and traffic pattern direction

should be used (Fig. 7-3).

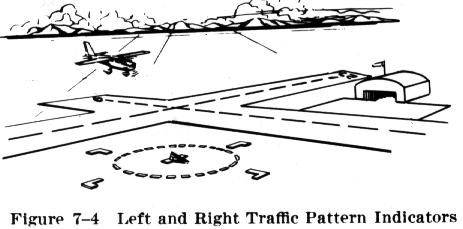

Many airports have L shaped traffic pattern indicators displayed with

a segmented circle adjacent to the runway. The short member of the L shows

the direction in which the traffic pattern turns should be made when using

the runway parallel to the long member. |

| For example, in Fig. 7-4, the airplane should fly a right

hand pattern. These indicators should, of course, be checked while at a

distance well away from any pattern that might be in use, or while at a

safe height well above generally used pattern altitudes. When the proper

traffic pattern direction has been determined, the pilot should then proceed

to a point well clear of the pattern before descending to the pattern altitude.

Generally, when approaching an airport for landing, the traffic pattern

should be entered at a 45 degree angle to the downwind leg, headed toward

a point abeam of the midpoint of the runway to be used for landing. |

|

Arriving airplanes should always be at the proper traffic

pattern altitude before entering the pattern, and should stay clear of

the traffic flow until established on the entry leg. Entries into traffic

patterns while descending create specific collision hazards and must be

avoided at all times.

The entry leg should be of sufficient length to provide

a clear view of the entire traffic pattern, and to allow the pilot adequate

time for planning the intended path in the pattern and the landing approach.