Night Vision

Night Vision

Generally, many persons are completely uninformed about

night vision, while others feel there is nothing to be learned about the

subject. Human eyes never function as effectively at night as the eyes

of animals with nocturnal habits, but if a human learns to use the eyes

correctly, night vision can be improved greatly. There are several reasons

for the training and practice necessary to use the eyes correctly.

One reason is that the mind and eyes act as a team for

a person to see well; both team members must be used effectively. Also,

the construction of the eyes is such that to see at night they must be

used differently than during the daytime. Therefore, it is important for

the pilot to understand the eye's construction and how the eye is affected

by darkness.

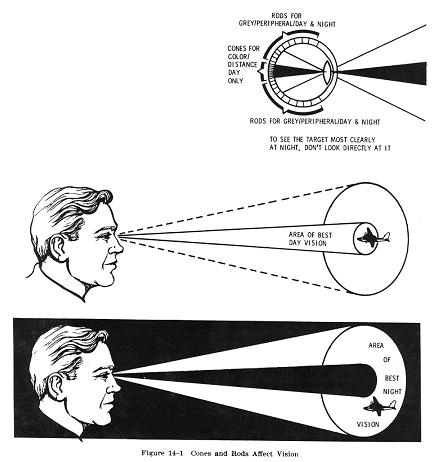

Innumerable light sensitive nerves, called "cones" and "rods," are

located at the back of the eye or retina, a layer upon which all images

are focused (Fig. 14-1). These nerves connect to the cells of the optic

nerve which transmit messages directly to the brain. The cones are located

in the center of the retina, and the rods are concentrated in a ring around

the cones.

The function of the cones is to detect color, details,

and far away objects. The rods function when something is seen out of the

corner of the eye - peripheral vision. They detect objects, particularly

those which are moving, but do not give detail or color - only shades of

gray. Both the cones and the rods are used for vision during daylight.

Although there is no clear cut division of function, generally

speaking, the rods make night vision possible. The rods and cones function

in daylight and in moonlight, but in the absence of these the process of

vision is placed almost entirely on the rods. |

|

The fact that the rods are distributed in a band around

the cones and do not lie directly behind the pupils, makes "off center"

viewing (looking to one side of an object) important during night flight

(Fig. 14-1). During daylight an object can be seen best by looking directly

at it, but at night a scanning procedure to permit "off center" viewing

of the object is more effective. Therefore, the pilot should consciously

practice this scanning procedure to improve night vision.

The eye's adaptation to darkness is another important aspect

of night vision. When a dark room is entered, it is difficult to see anything

until the eyes become adjusted to the darkness. Most everyone has experienced

this after entering a darkened movie theater. In this process, the pupils

of the eyes first enlarge to receive as much of the available light as

possible. After approximately 5 to 10 minutes, the cones become adjusted

to the dim light and the eyes become 100 times more sensitive to the light

than they were before the dark room was entered. Much more time, about

30 minutes, is needed for the rods to become adjusted to darkness; but

when they do adjust they are about 100,000 times more sensitive to light

than they were in the lighted area. After the adaptation process is complete

much more can be seen, especially if the eyes are used correctly.

This entire process is reversed when a bright area is entered from a

dark room. The eyes are first dazzled by the brightness, but become completely

adjusted in a very few seconds, thereby losing their adaptation to the

dark. Now, if the dark room is reentered, the eyes must again go through

the long process of adapting to the darkness.

The adaptation process of the eyes must be considered by

the pilot before and during night flight. First the eyes must be allowed

to adapt to the low level of light and then they must be kept adapted.

After the eyes have become adapted to darkness, the pilot must avoid exposing

them to any bright white light which will cause temporary blindness and

could result in serious consequences.

Temporary blindness caused by an unusually bright light,

may result in illusions or "after images" during the time the eyes are

recovering from the brightness. The brain creates these illusions reported

by the eyes. This results in misjudging or incorrectly identifying objects,

such as mistaking slanted clouds for the horizon or populated areas for

a landing field. Vertigo is experienced by the pilot as a feeling of dizziness

and imbalance which in itself can create or increase illusions. The illusions

seem very real and pilots of any level of experience and skill can be affected.

Recognizing that the brain and eyes can play tricks in this manner is the

best protection for the pilot flying at night.

Good eyesight depends upon physical condition. Fatigue,

colds, vitamin deficiency, alcohol, stimulants, smoking, or medication

can seriously impair the pilot's vision. Keeping these facts in mind and

taking adequate precautions should safeguard the pilot's night vision.

In review and in addition to the principles previously

discussed, the following will aid the pilot in increasing night vision

effectiveness:

1. Adapt the eyes to darkness prior to

flight and keep them adapted. About 30 minutes is needed to adjust the

eyes to maximum efficiency after exposure to a bright light.

2. Close one eye when exposed to bright

light to help avoid the blinding effect.

3. Do not wear sunglasses after sunset.

4. Move the eyes more slowly than in

daylight.

5. Blink the eyes if they become blurred.

6. Concentrate on seeing objects.

7. Force the eyes to view off center.

8. Maintain good physical condition.

9. Avoid smoking, drinking, and using

drugs which may be harmful.