APPROACH TO LANDING

No other aircraft has as many different types of

landings as a balloon. Most aircraft, including gliders

and helicopters, land on relatively smooth, hard

places. Balloons rarely land on smooth, hard places.

Since the balloon is stronger than people are and less

susceptible to damage, a soft landing is one that is

judged to be easy on the passengers.

Birds are probably the only flying things that have

more available landing sites. Balloons can land safely

in places that most other aircraft cannot. Balloons

can land on the ground or in the water, on the flat or

side of a hill, in bushes or trees (with maybe a little

damage), on plowed and irrigated fields, in snow or

mud. There is an infinite variety of suitable balloon

landing sites and rarely are two balloon landings alike.

When a landing site is being considered, you should

first think about the suitability of the site. “Is it safe,

is it legal, and is it polite?” When considering surface

winds, you should make certain there is adequate

access to the site with respect to obstructions.

Some Basic Rules of Landing

The final, safe resting place of the balloon is a major

consideration in landing. Making a soft landing is not

as important as getting the balloon where you want it.

Having an easy retrieval is not as important as an

accident-free, appropriate landing site.

Plan the landing early enough so that fuel quantity

is not a distraction. Plan on landing with enough

fuel so that even if your first approach to a landing

site is unsuccessful, there is enough fuel to make a

couple more approaches.

The best landing site is one that is bigger than you

need and has alternatives. If you have three

prospective sites in front of you, aim for the one in

the middle in case your surface wind estimate was

off. If you have multiple prospective landing sites

in a row along your path, take the first one and

save the others for a miscalculation. Unless there

is a 180° turn available, all the landing sites behind

are lost.

The best altitude for landing is the lowest altitude.

Anyone can land from 1 foot above the ground; it

takes skill to land from 100 feet.

A low approach, assuming no obstacles, gives you

the slowest touchdown speed because the winds

are usually lightest close to the ground.

It is usually better to fly over an obstacle and land

beyond it than to land in front of it. Overfly

powerlines, trees, and water, among other

obstacles, on the way to the landing, rather than

attempting to land in front of them and risk being

dragged into them.

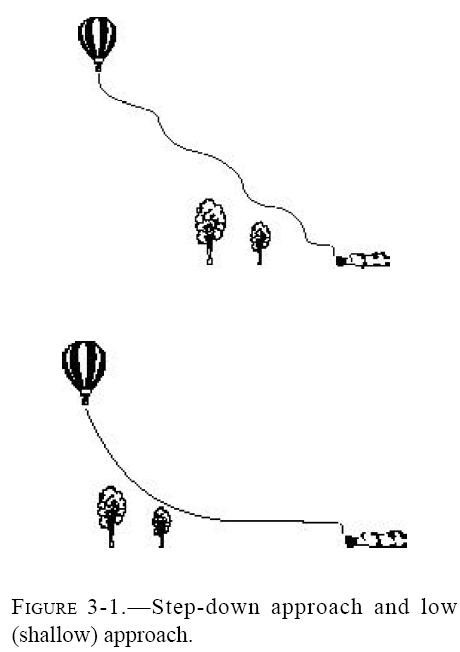

Before beginning your approach, plan to fly a

reasonable descent path to the landing site, using

the step-down approach method, the low (shallow)

approach method, or a combination of the two.

[Figure 3-1]

|