|

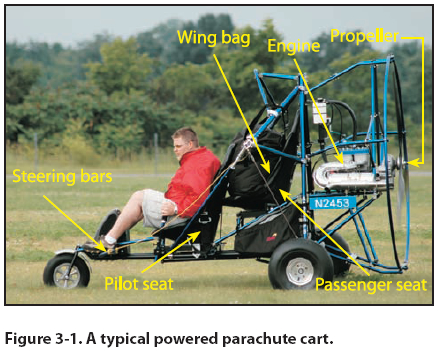

Although powered parachutes come in an array of

shapes and sizes, the basic design features are fundamentally

the same. All powered parachutes consist

of an airframe (referred to as a cart) a propeller

powered by an engine, and a ram-air inflated wing.

[Figure 3-1]

The Airframe

Most powered parachute airframes are manufactured

with aircraft-grade hardware. A few PPC manufacturers

are building fiber-composite carts. The airframe’s

tubular construction means light weight and ease of

replacement if tubes are bent. The airframe includes

one or two seats, flight controls, and an instrument

panel. The airframe also incorporates the engine, the

fuel tank, the propeller and points of attachment for

the wing and steering lines.

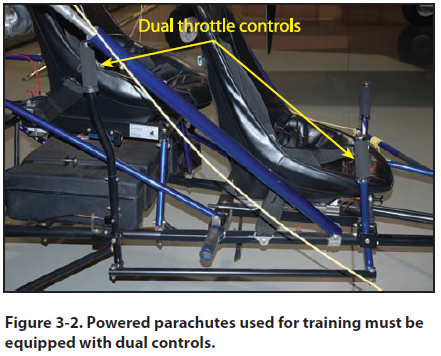

Although side-by-side configurations exist, in most

powered parachutes the pilot and passenger are seated

in a tandem (fore and aft) configuration. Dual flight

controls are required for training. Not all PPCs have

full dual controls; depending on the configuration of

the cart and added controls (that are optional from

different airframe manufacturers) the flight instructor

can adequately control the aircraft during training

from the rear seat during takeoff, flight, and landing

procedures with dual throttle controls. While in the rear seat, the flight instructor can have positive control

of the aircraft at all times by physically pulling

on the steering lines and using a dual control throttle.

Like airplanes, not all powered parachutes are adequately

configured to conduct flight training. The

flight instructor with a powered parachute endorsement

should determine his or her ability to control

each individual PPC from the back seat with the dual

controls for training purposes. [Figure 3-2]

The pilot flies from the front seat in order to reach the

steering bars, throttle control, ground steering control

and magneto switches, and to keep the CG in balance;

you cannot fly alone from the back seat for this reason.

The cart by itself is not very aerodynamic because

it does not need to be; it flies at slower airspeeds.

However, without the wing attached and inflated to

limit speed, the pilot needs to be careful to avoid high

speeds, such as when taxiing to and from the hangar

for canopy layout. The wheels, their bearings, and

the cart suspension were not designed to handle high

speeds.

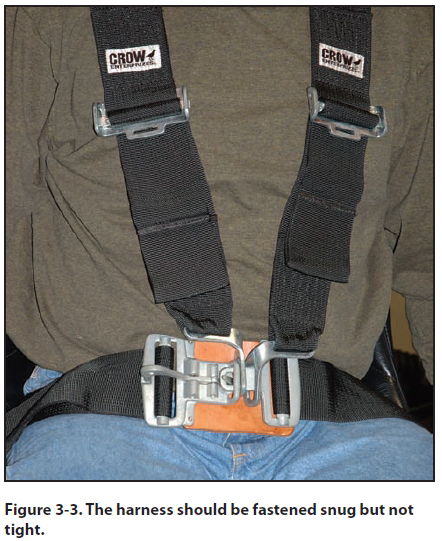

Some manufacturers use an adjustable front seat

to allow for the varied length of the pilot’s legs

to comfortably reach the steering bars. Powered parachutes can be outfitted with a variety of seatbelts,

including a four-point harness system that

securely fastens each occupant into their seat.

[Figure 3-3]

Most powered parachutes have three wheels, or a tricycle

gear configuration, although some have four.

Ground steering is typically a steering bar connected

to the nosewheel that moves left and right. Some powered

parachutes have a tiller device for ground steering.

There are a number of ground steering designs

that vary between manufacturer, make, and model.

Brakes are an optional piece of equipment on the

powered parachute, as the square foot area of the

parachute itself provides aerodynamic braking. Pilots

should use smooth and controlled operation of the

throttle on the ground to maintain safe and controllable

ground speeds, particularly when taxiing with

the chute inflated. Students should practice throttle

control to learn how far the PPC takes to come to a

full stop when the power is reduced to idle. However,

for runway incursion prevention and general safety,

brakes are advised and highly recommended so you

can stop when you need to. Never use your feet as a

form of braking, as physical injury is probable.

|