In spite of the remarkable reliability of present day airplane engines, the pilot should always be prepared to cope with emergencies which may involve a forced landing caused by partial or complete engine failure.

A study by the National Transportation Safety Board reveals several factors that may interfere with a pilot's ability to act promptly and properly when faced with such an emergency:

1. Reluctance to Accept the Emergency Situation: A pilot whose mind is allowed to become paralyzed at the thought that the aircraft will be on the ground in a short time, regardless of what is done, is severely handicapped in the handling of the emergency. An unconscious desire to delay this dreaded moment may lead to such errors as failure to lower the nose to maintain flying speed, delay in the selection of the most suitable touchdown area within reach, and indecision in general.

2. Desire to Save the Aircraft: A pilot who has been conditioned to expect to find a relatively safe landing area whenever the instructor closed the throttle for a simulated forced landing may ignore all basic rules of airmanship to avoid a touchdown in terrain where aircraft damage is unavoidable. The desire to save the aircraft, regardless of the risks involved, may be influenced by the pilot's financial stake in the aircraft and the certainty that an undamaged aircraft implies no bodily harm. There are times when a pilot should be more interested in sacrificing the aircraft so that all occupants can safely walk away from it.

3. Undue Concern About Getting Hurt: Fear is a vital part of our self-preservation mechanism. When fear leads to panic we invite that which we want to avoid the most. The survival records favor those who maintain their composure and know how to apply the general concepts and techniques that have been developed throughout the years.

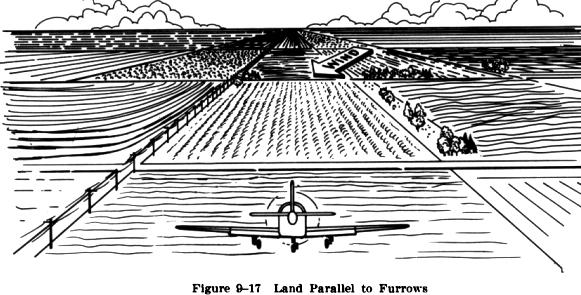

A competent pilot is constantly on the alert for suitable forced landing fields. Naturally, the perfect forced landing field is an established airport, or a hard packed, long smooth field with no high obstacles on the approach end; however, these ideal conditions may not be readily available, so the best available field must be selected. Cultivated fields are usually satisfactory, and plowed fields are acceptable if the landing is made parallel to the furrows (Fig. 9-17). In any case, fields in which there are large boulders, ditches, or other features which present a hazard during the landing, should be avoided. A landing with the landing gear retracted may be advisable in soft or snow covered fields to eliminate the possibility of the airplane nosing over, or damaging the gear, as a result of the wheels digging in.

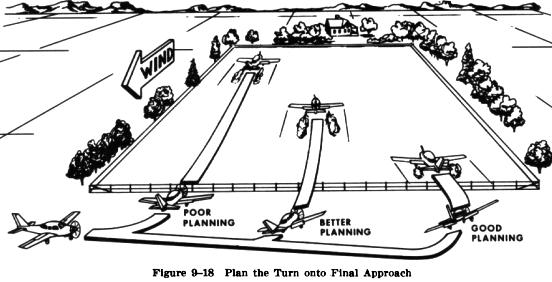

Several factors must be considered in determining whether a field is of adequate length. When landing on a level field into a strong headwind, the distance required for a safe landing will naturally be much less than the distance required for landing with a tailwind. If it is impossible to land directly into the wind because maneuvering to an upwind approach would place the airplane at a dangerously low altitude, or a suitable field into the wind is not available, then the landing should be made crosswind or downwind. A large field that is crosswind, or even downwind, may be safer than a smaller field which is directly into the wind. Whenever possible the pilot should select a field that is wide enough to allow extending the base leg and delaying the turn onto the final approach to correct for any error in planning (Fig. 9-18).

The direction and speed of the wind are important factors during any landing, particularly in a forced landing, since the wind affects the airplane's gliding distance over the ground, the path over the ground during the approach, the groundspeed at which the airplane contacts the ground, and the distance the airplane rolls after the landing. All these effects should be considered during the selection of a field.

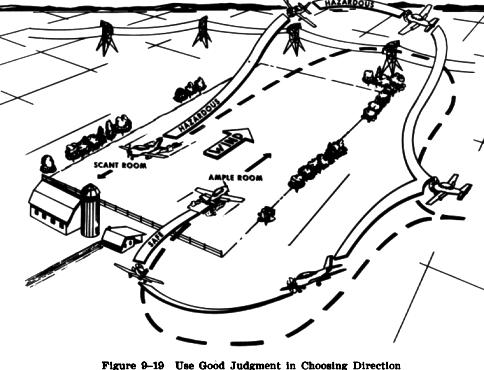

As a general rule, all landings should be made with the

airplane headed into the wind, but this cannot be a hard and fast rule,

since many other factors may make it inadvisable in the case of an actual

forced landing (Fig. 9-19). Examples of such factors are:

1. Insufficient altitude may make it

inadvisable or impossible to attempt to maneuver into the wind.

2. Ground obstacles may make landing into the wind impractical or inadvisable because they shorten the effective length of the available field.

3. Distance from a suitable field upwind from the present position may make it impossible to reach the field from the altitude at which the engine failure occurs.

4. The best available field may be downhill

and at such an angle to the wind that a downwind landing uphill would be

preferable and safer.

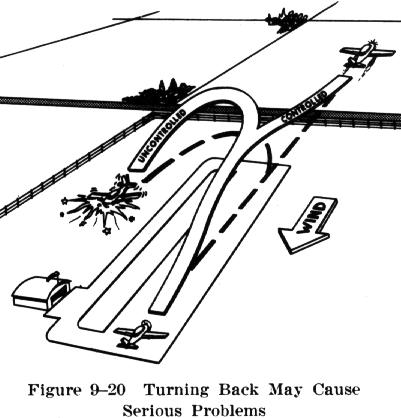

| The altitude available is, in many ways, the controlling

factor in the successful accomplishment of a forced landing. If an actual

engine failure should occur immediately after takeoff and before a safe

maneuvering altitude is attained, it is usually inadvisable to attempt

to turn back to the field from which the takeoff was made (Fig. 9-20).

Instead, it is generally safer to immediately establish the proper glide

attitude, and select a field directly ahead or slightly to either side

of the takeoff path.

The decision to continue straight ahead is often a difficult one to make unless the problems involved in attempting to turn back are seriously considered. In the first place, the takeoff was in all probability made into the wind. To get back to the takeoff field, a downwind turn must be made. This, of course, increases the groundspeed and rushes the pilot even more in the performance of procedures and in planning the landing approach. Secondly, the airplane will be losing considerable altitude during the turn and might still be in bank when the ground is contacted, thus resulting in the airplane cartwheeling (which would be a catastrophe for the occupants as well as the |

|

When a forced landing is imminent, wind direction and speed should always be considered, but the main object is to complete a safe landing in the largest and best field available. This involves getting the airplane on the ground in as near a normal landing attitude as possible without striking obstructions. If the pilot gets the airplane on the ground under control, it may sustain damage, but the occupants will probably get no worse than a shaking up.

During actual forced landings, it is recommended that the airplane be maneuvered to conform with a 360 degree overhead approach, a 180 degree side approach, a 90 degree approach, or a straight-in approach, with whatever modifications are necessary. These approaches are described later in this chapter.