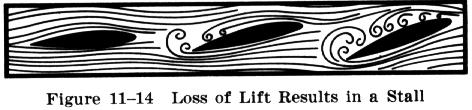

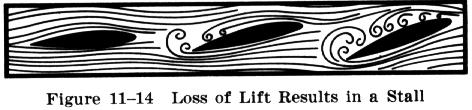

A stall occurs when the smooth airflow over the airplane's wing is disrupted, and the lift degenerates rapidly (Fig. 11-14). This can occur AT ANY AIRSPEED, IN ANY ATTITUDE, WITH ANY POWER SETTING.

The practice of stall recovery and the development of awareness of imminent stalls are of primary importance in pilot training. The objectives in performing intentional stalls are to familiarize the pilot with the conditions that produce stalls, to assist in recognizing an approach stall, and to develop the habit of taking prompt preventive or corrective action.

To become proficient, pilots must recognize the flight conditions that are conducive to stalls and know how to apply the necessary corrective action. They should learn to recognize an approaching stall by sight, sound, and feel. The following cues may be useful in recognizing the approaching stall:

1. Vision is useful in detecting a stall condition by noting the attitude of the airplane. This sense can be fully relied on only when the stall is the result of an unusual attitude of the airplane. However, since the airplane can also be stalled from a normal attitude, vision in this instance would be of little help in detecting the approaching stall.

2. Hearing is also helpful in sensing a stall condition, since the tone level and intensity of sounds incident to flight decrease as the airspeed decreases. In the case of fixed pitch propeller airplanes in a power on condition, a change in sound due to loss of RPM is particularly noticeable. The lessening of the nose made by the air flowing along the airplane structure as airspeed decreases is also quite noticeable, and when the stall is almost complete, vibration and its incident noises often increase greatly.

3. Kinesthesia, or the sensing of changes in direction or speed of motion, is probably the most important and the best indicator to the trained and experienced pilot. If this sensitivity is properly developed, it will warn of a decrease in speed or the beginning of a settling or "mushing" of the airplane.

4. The feeling of control pressures is also very important. As speed is reduced the "live" resistance to pressures on the controls becomes progressively less. Pressures exerted on the controls tend to become movements of the control surfaces, and the lag between those movements and the response of the airplane becomes greater, until in a complete stall all controls can be moved with almost no resistance, and with little immediate effect on the airplane.

Intentional stalls should be performed at an altitude that will provide adequate height above the ground for recovery and return to normal level flight. Though it depends on the degree to which a stall has progressed, most stalls require some loss of altitude during recovery. The longer it takes to sense the approaching stall, the more complete the stall is likely to become, and the greater the loss of altitude to be expected.

Several types of stall warning indicators have been developed that warn the pilot of an approaching stall. The use of such indicators is valuable and desirable, but the reason for practicing stalls is to learn to recognize stalls without the benefit of warning devices.