This maximum performance operation requires the use of procedures and techniques for the approach and landing at fields which have a relatively short landing area or where an approach must be made over obstacles which limit the available landing area. As in short field takeoffs, it is one of the most critical of the maximum performance operations, since it requires that the pilot fly the airplane at one of its crucial performance capabilities while close to the ground in order to safely land within confined areas. This low speed type of power on approach is closely related to the performance of "flight at minimum controllable airspeeds" described in the chapter on Proficiency Flight Maneuvers.

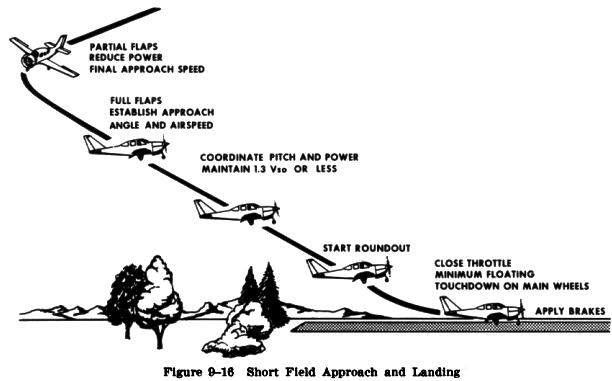

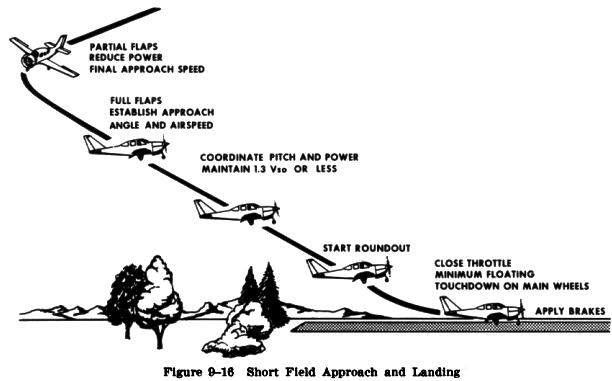

In the performance of power off type approaches and landings, it is not always possible to predict the exact spot where the airplane will touch down - due to airspeed and rate or angle of descent variations caused by wind, up and down drafts, pitch changes, and floating after roundout. However, to land within a short field or a confined area, the pilot must have precise, positive control of the rate of descent and airspeed to produce an approach that will clear any obstacles, result in little or no floating during the roundout, and permit the airplane to be stopped in the shortest possible distance (Fig. 9-16).

The procedures for landing in a short field or for landing approaches over 50 foot obstacles as recommended in the FAA approved Airplane Flight Manual or the Pilot's Operating Handbook, should be used. These procedures generally involve the use of full flaps, and the final approach started from an altitude of at least 500 feet higher than the touchdown area. In the absence of the manufacturer's recommended approach speed, a speed of not more than 1.3 Vs0 should be used - that is, in an airplane which stalls at 60 knots with power off and flaps and landing gear extended, the approach speed should be no higher than 78 knots. In gusty air, no more than one-half the gust factor may be added. An excessive amount of airspeed could result in touchdown too far from the runway threshold or an after landing roll that exceeds the available landing area.

After the landing gear and full flaps have been extended, the pilot should simultaneously adjust the power and the pitch attitude to establish and maintain the proper descent angle and airspeed.

Since short field approaches are power on approaches, the pitch attitude is adjusted as necessary to establish and maintain the desired rate or angle of descent, and power is adjusted to maintain the desired airspeed. However, a coordinated combination of both pitch and power adjustments is usually required. When this is done properly, very little change in the airplane's pitch attitude is necessary to make corrections in the angle of descent and only small power changes are needed to control the airspeed.

If it appears that the obstacle clearance is excessive and touchdown would occur well beyond the desired spot leaving insufficient room to stop, power may be reduced while lowering the pitch attitude to increase the rate of descent. If it appears that the descent angle will not ensure safe clearance of obstacles, power should be increased while simultaneously raising the pitch attitude to decrease the rate of descent. Care must be taken, however, to avoid an excessively low airspeed. If the speed is allowed to become too slow, an increase in pitch and application of full power may only result in a further rate of descent. This occurs when the angle of attack is so great and creating so much drag that the maximum available power is insufficient to overcome it. This is generally referred to as operating in the "region of reverse command" or operating on the "back side of the power curve."

Because the final approach over obstacles is made at a steep approach angle and close to the airplane's stalling speed, the initiation of the roundout or flare must be judged accurately to avoid flying into the ground, or stalling prematurely and sinking rapidly. A lack of floating during the flare, with sufficient control to touch down properly, is one verification that the approach speed was correct.

Touchdown should occur at the minimum controllable airspeed

with the airplane in approximately the pitch attitude which will result

in a power off stall when the throttle is closed. Care must be exercised

to avoid closing the throttle rapidly before the pilot is ready for touchdown,

as closing the throttle may result in an immediate increase in the rate

of descent and a hard landing.

Upon touchdown, nosewheel type airplanes should be held

in this positive pitch attitude as long as the elevators remain effective,

and tailwheel type airplanes should be firmly held in a three point attitude.

This will provide aerodynamic braking by the wings.

Immediately upon touchdown, and closing the throttle, the brakes should be applied evenly and firmly to minimize the after landing roll. The airplane should be stopped within the shortest possible distance consistent with safety.