Taxiing is the controlled movement of the airplane under its own power while on the ground. Since an airplane must be moved under its own power between the parking area and the runway, the pilot must thoroughly understand taxiing procedures and be proficient in maintaining positive control of the airplane's direction and speed of movement on the ground. In addition, the pilot must be alert and visually check the location and movements of everything else along the taxi path.

An awareness of other aircraft which are taking off, landing, or taxiing, and consideration for the right of way of others is essential to safety. To really observe the entire area, the pilot's eyes must cover almost a complete circle. While taxiing, the pilot must be sure the airplane's wings will clear all obstructions and other aircraft. If at any time there is doubt about the clearance of the wingtips, the pilot should stop the airplane and have someone check the amount of clearance from the object. If no help is available, the engine should be shut down. It may be necessary to have the airplane physically moved by a ground crew.

It is difficult to set any rule for a safe taxiing speed. What is safe under some conditions may be hazardous under others. The primary requirement of safe taxiing is safe positive control; the ability to stop or turn where and when desired. Normally, the speed should be at the rate where movement of the airplane is dependent on the throttle; that is, slow enough so when the throttle is closed the airplane can be stopped promptly.

Except while taxiing very slowly, it is best to slow down before attempting a turn. Otherwise, the turn may have too great a radius or could result in an uncontrollable swerve or a ground loop. The latter is most likely to occur when turning from a downwind heading to an upwind heading, due to the airplane's tendency to "weathervane" when the airplane is headed cross wind. This tendency is explained in more detail in the chapter "Landing Approaches and Landings." When turning from an upwind heading to a downwind heading, however, this precaution is not as important, since the weathervane tendency will usually cause a deceleration in the rate of turn.

Very sharp turns or attempting to turn at too great a speed must be avoided as both tend to exert excessive strains on the airplane, and such turns are difficult to control, once started. Many airplanes, particularly those with a short distance between the wheels, have a tendency to tip over and drag a wing tip on the ground, causing serious damage.

Since airplane flight control surfaces are designed for maximum effectiveness in flight, they have limited use during the airplane's movement on the ground. At normal taxi speeds, air pressures will usually not be felt on the control surface as they will during flight.

When taxiing at normal taxi speeds in a no wind condition, the aileron and elevator control surfaces have little or no effect on directional control of the airplane and therefore should not be considered steering devices. Remember, the flight control's effect on the airplane is the result of pressure exerted by the airflow. Very little air pressure is created by the airflow from an idling propeller or from the slow forward movement of the airplane at a low taxi speed. Since the ailerons and elevator are not helpful in a no wind condition, they should be held in neutral positions. Their use when taxiing in windy conditions will be discussed later.

The rudder pedals are the primary directional controls

while taxiing. Steering with the pedals may be accomplished through the

forces of airflow or propeller slipstream acting on the rudder surface,

or through a mechanical linkage to the steerable nosewheel or tailwheel.

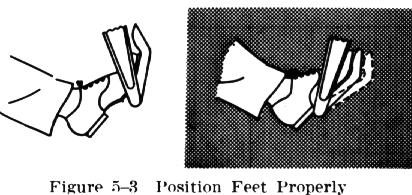

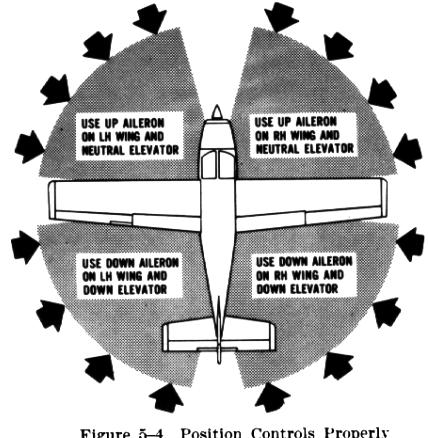

| Initially, the pilot should taxi with the heels of the feet resting on the cockpit floor and the balls of the feet on the bottom of the rudder pedals (Fig. 5-3). The feet should be slid up onto the brake pedals only when it is necessary to depress the brakes. Only after considerable experience is gained, should the feet be positioned with the arches placed on the rudder pedals and the toes near but not quite touching the brake portion of the pedals. This permits the simultaneous application of rudder and brake whenever needed. The brakes are used primarily to stop the airplane at a desired point, to slow the airplane, or as an aid in making a sharp controlled turn. Whenever used, they must be applied smoothly, evenly, and cautiously at all times. |

|

More engine power may be required to start the airplane moving forward, or to start or stop a turn, than is required to keep it moving in any given direction. Therefore, there may be times when it is necessary to use a comparatively large amount of power. When used, the throttle should immediately be retarded once the airplane begins moving, to prevent accelerating too rapidly.

When first starting to taxi, the brakes should be tested immediately for proper operation. This is done by first applying power to start the airplane moving slowly forward, then retarding the throttle and simultaneously applying pressure smoothly to both brakes. If braking action is unsatisfactory, the engine should be shut down immediately.

To turn the airplane on the ground, the pilot should apply rudder in the desired direction of turn and use whatever power or brake that is necessary to control the taxi speed. The rudder should be held in the direction of the turn until just short of the point where the turn is to be stopped, then the rudder pressure released or slight opposite pressure applied as needed.

While taxiing, the pilot will have to anticipate the movements

of the airplane and adjust rudder pressure accordingly. Since the airplane

will continue to turn slightly even as the rudder pressure is being released,

the stopping of the turn must be anticipated and the rudder pedals neutralized

before the desired heading is reached. In some cases, it may be necessary

to apply opposite rudder to stop the turn, depending on the taxi speed.

|

Usually when operating on a soft or muddy field, the taxi speed or

power must be maintained slightly above that required under normal field

conditions. Otherwise, the drag of the surface may cause the airplane to

stop before adequate power can be applied to keep it in motion. This may

require the use of full power in getting underway again, causing mud or

stones to be picked up by the propeller, resulting in damage. When an airplane

is allowed to stop under these conditions, it may be impossible to start

moving again with its own power. On soft surfaces, such as turf, sand,

or snow, the use of additional power will result in more blast on the airplane's

tail, and consequently better rudder control.

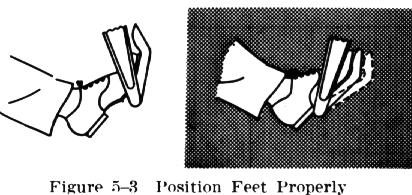

The presence of moderate to strong headwinds and/or a strong propeller

slipstream makes the use of the elevator necessary to maintain control

of the pitch attitude while taxiing. This becomes apparent when considering

the lifting action that may be created on the horizontal tail surfaces

by either of those two factors. The elevator control in nosewheel type

airplanes should be held in the neutral position, while in tailwheel type

airplanes it should be held in the aft position to hold the tail down (Fig.

5-4).

|

| When taxiing in a crosswind, the wing on the upwind side usually will

tend to be lifted by the wind unless the aileron control is held in that

direction (upwind aileron UP). Moving the aileron into the UP position

reduces the effect of wind striking that wing, thus reducing the lifting

action. This control movement will also cause the opposite aileron to be

placed in the down position, thus creating drag and possibly some lift

on the downwind wing, further reducing the tendency of the upwind wing

to rise.

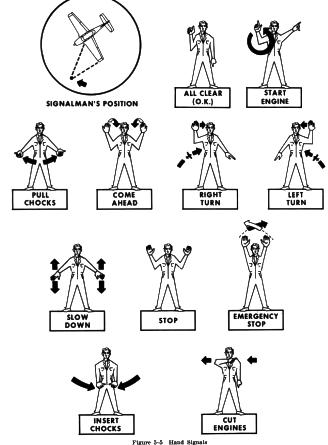

When taxiing with a quartering tailwind, the elevator should be held in the down or neutral position, and the upwind aileron down. Since the wind is striking the airplane from behind, these control positions reduce the tendency of the wind to get under the tail and the wing and to nose the airplane over. The application of these crosswind taxi corrections also helps to minimize the weathervaning tendency and ultimately result in making the airplane easier to steer. In addition to learning taxiing techniques, all pilots should learn the standard hand signals used by ramp attendants for the direction of pilots operating airplanes in the parking area. These are shown in Fig. 5-5. |

|