| Chapter 9. Risk Management

The PAVE Checklist

Another way to mitigate risk is to perceive hazards. By incorporating the PAVE checklist into all stages of flight planning, the pilot divides the risks of flight into four categories: Pilot in command (PIC), Aircraft, enVironment, and External pressures (PAVE) which form part of a pilot’s decision-making process.

With the PAVE checklist, pilots have a simple way to remember each category to examine for risk prior to each flight. Once a pilot identifies the risks of a flight, he or she needs to decide whether the risk or combination of risks can be managed safely and successfully. If not, make the decision to cancel the flight. If the pilot decides to continue with the flight, he or she should develop strategies to mitigate the risks. One way a pilot can control the risks is to set personal minimums for items in each risk category. These are limits unique to that individual pilot’s current level of experience and proficiency.

For example, the aircraft may have a maximum crosswind component of 15 knots listed in the aircraft flight manual (AFM), and the pilot has experience with 10 knots of direct crosswind. It could be unsafe to exceed a 10 knots crosswind component without additional training. Therefore, the 10 kts crosswind experience level is that pilot’s personal limitation until additional training with a certificated flight instructor (CFI) provides the pilot with additional experience for flying in crosswinds that exceed 10 knots.

One of the most important concepts that safe pilots understand is the difference between what is “legal” in terms of the regulations, and what is “smart” or “safe” in terms of pilot experience and proficiency.

P = Pilot in Command (PIC)

The pilot is one of the risk factors in a flight. The pilot must ask, “Am I ready for this trip?” in terms of experience, currency, physical and emotional condition. The IMSAFE checklist combined with proficiency, recency, and currency provides the answers.

A = Aircraft

What limitations will the aircraft impose upon the trip? Ask the following questions:

- Is this the right aircraft for the flight?

- Am I familiar with and current in this aircraft? Aircraft performance figures and the AFM are based on a brand new aircraft flown by a professional test pilot. Keep that in mind while assessing personal and aircraft performance.

- Is this aircraft equipped for the flight? Instruments? Lights? Navigation and communication equipment adequate?

- Can this aircraft use the runways available for the trip with an adequate margin of safety under the conditions to be flown?

- Can this aircraft carry the planned load?

- Can this aircraft operate at the altitudes needed for the trip?

- Does this aircraft have sufficient fuel capacity, with reserves, for trip legs planned?

- Does the fuel quantity delivered match the fuel quantity ordered?

V = EnVironment

Weather is an major environmental consideration. Earlier it was suggested pilots set their own personal minimums, especially when it comes to weather. As pilots evaluate the weather for a particular flight, they should consider the following:

- What are the current ceiling and visibility? In mountainous terrain, consider having higher minimums for ceiling and visibility, particularly if the terrain is unfamiliar.

- Consider the possibility that the weather may be different than forecast. Have alternative plans, and be ready and willing to divert should an unexpected change occur.

- Consider the winds at the airports being used and the strength of the crosswind component.

- If flying in mountainous terrain, consider whether there are strong winds aloft. Strong winds in mountainous terrain can cause severe turbulence and downdrafts and can be very hazardous for aircraft even when there is no other significant weather.

- Are there any thunderstorms present or forecast?

- If there are clouds, is there any icing, current or forecast? What is the temperature-dew point spread and the current temperature at altitude? Can descent be made safely all along the route?

- If icing conditions are encountered, is the pilot experienced at operating the aircraft’s deicing or anti-icing equipment? Is this equipment in good condition and functional? For what icing conditions is the aircraft rated, if any?

Evaluation of terrain is another important component of analyzing the flight environment. To avoid terrain and obstacles, especially at night or in low visibility, determine safe altitudes in advance by using the altitudes shown on VFR and IFR charts during preflight planning. Use maximum elevation figures (MEFs) and other easily obtainable data to minimize chances of an inflight collision with terrain or obstacles.

Airport considerations include:

- What lights are available at the destination and alternate airports? VASI/PAPI or ILS glideslope guidance? Is the terminal airport equipped with them? Are they working? Will the pilot need to use the radio to activate the airport lights?

- Check the Notices to Airmen (NOTAMs) for closed runways or airports. Look for runway or beacon lights out, nearby towers, etc.

- Choose the flight route wisely. An engine failure gives the nearby airports (and terrain) supreme importance.

- Are there shorter or obstructed fields at the destination and/or alternate airports?

Airspace considerations include:

- If the trip is over remote areas, are appropriate clothing, water, and survival gear onboard in the event of a forced landing?

- If the trip includes flying over water or unpopulated areas with the chance of losing visual reference to the horizon, the pilot must be current, equipped, and qualified to fly IFR.

- Check the airspace and any temporary flight restriction (TFRs) along the route of flight.

Night flying requires special consideration.

- If the trip includes flying at night over water or unpopulated areas with the chance of losing visual reference to the horizon, the pilot must be prepared to fly IFR.

- Will the flight conditions allow a safe emergency landing at night?

- Preflight all aircraft lights, interior and exterior, for a night flight. Carry at least two flashlights—one for exterior preflight and a smaller one that can be dimmed and kept nearby.

E = External Pressures

External pressures are influences external to the flight that create a sense of pressure to complete a flight—often at the expense of safety. Factors that can be external pressures include the following:

- Someone waiting at the airport for the flight’s arrival.

- A passenger the pilot does not want to disappoint.

- The desire to demonstrate pilot qualifications.

- The desire to impress someone. (Probably the two most dangerous words in aviation are “Watch this!”)

- The desire to satisfy a specific personal goal (“get-home-itis,” “get-there-itis,” and “let’s-go-itis”).

- The pilot’s general goal-completion orientation.

- Emotional pressure associated with acknowledging that skill and experience levels may be lower than a pilot would like them to be. Pride can be a powerful external factor!

Management of external pressure is the single most important key to risk management because it is the one risk factor category that can cause a pilot to ignore all the other risk factors. External pressures put time-related pressure on the pilot and figure into a majority of accidents.

The use of personal standard operating procedures (SOPs) is one way to manage external pressures. The goal is to supply a release for the external pressures of a flight. These procedures include but are not limited to:

- Allow time on a trip for an extra fuel stop or to make an unexpected landing because of weather.

- Have alternate plans for a late arrival or make backup airline reservations for must-be-there trips.

- For really important trips, plan to leave early enough so that there would still be time to drive to the destination.

- Advise those who are waiting at the destination that the arrival may be delayed. Know how to notify them when delays are encountered.

- Manage passengers’ expectations. Make sure passengers know that they might not arrive on a firm schedule, and if they must arrive by a certain time, they should make alternative plans.

- Eliminate pressure to return home, even on a casual day flight, by carrying a small overnight kit containing prescriptions, contact lens solutions, toiletries, or other necessities on every flight.

The key to managing external pressure is to be ready for and accept delays. Remember that people get delayed when traveling on airlines, driving a car, or taking a bus. The pilot’s goal is to manage risk, not create hazards.

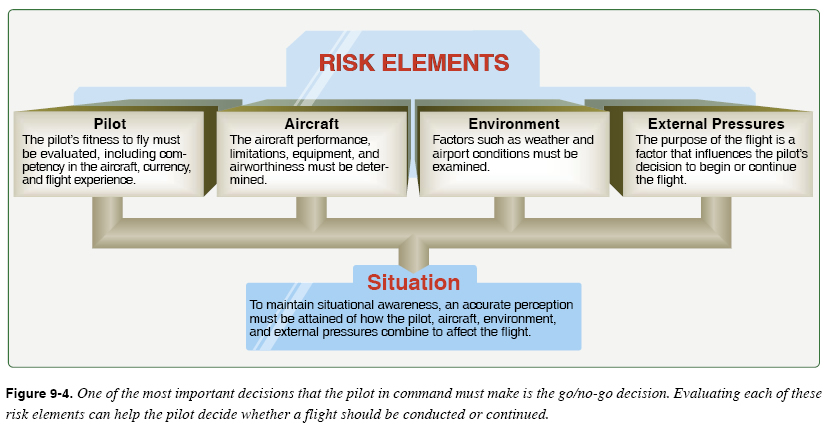

During each flight, decisions must be made regarding events involving interactions between the four risk elements—PIC, aircraft, environment, and external pressures. The decision-making process involves an evaluation of each of these risk elements to achieve an accurate perception of the flight situation. [Figure 9-4]

|