|

Chapter 11 — Approaches and Landings

Turbulent Air Approach and Landing

Powered parachute flying is a low-wind sport. It is important

PPC pilots evaluate the upper-air winds to ensure

the wind is within the limitations for that aircraft,

accounting for wind shear and wind gust possibilities

at pattern altitude.

For flying in more turbulent air on final approach,

maintain power throughout the approach to reduce

your descent rate in case you do experience a down

gust. This will alleviate the possibility of an excessive

descent rate.

Emergency Approaches and

Landings (Simulated)

From time to time on dual flights, the instructor should

give simulated emergency landings by retarding the

throttle and calling “simulated emergency landing.”

The objective of these simulated emergency landings

is to develop the pilot’s accuracy, judgment, planning,

procedures, and confidence when little or no power is

available.

A simulated emergency landing may be given at any

time. When the instructor calls “simulated emergency

landing,” the pilot should consider the many variables,

such as altitude, obstruction, wind direction, landing

direction, landing surface and gradient, and landing

distance requirements. Risk management must be exercised

to determine the best outcome for the given

set of circumstances. The higher the altitude, the more

time the pilot has to make the decision of where to

land.

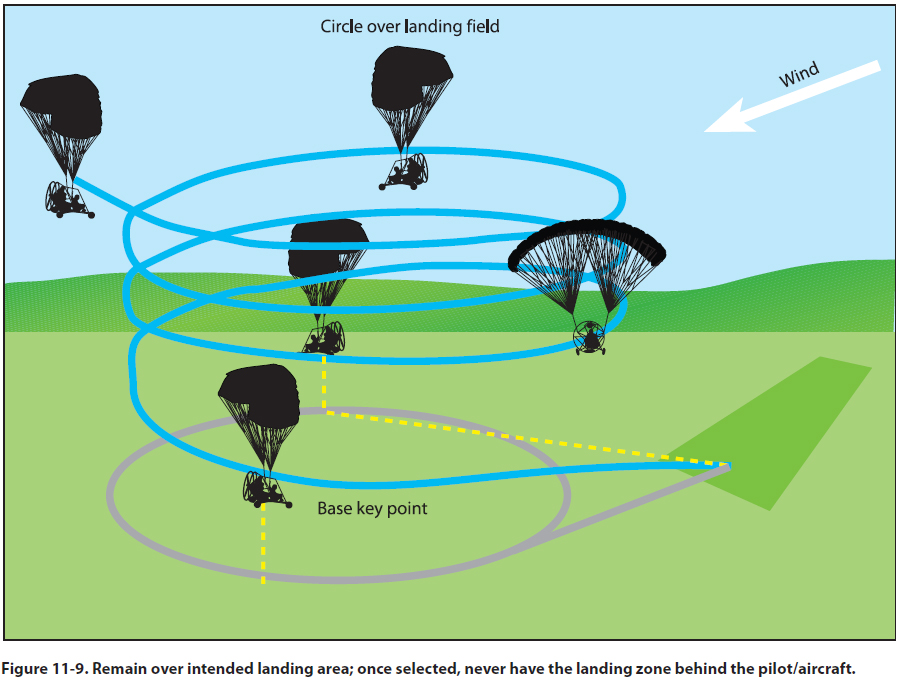

Using any combination of normal gliding maneuvers,

from wing level to turns, the pilot should eventually

arrive at the normal key position at a normal traffic

pattern altitude for the selected landing area. From

this point on, the approach will be as nearly as possible

a normal power-off approach. [Figure 11-9]

All pilots should learn to determine the wind direction

and estimate its speed. This can be done by observing

the windsock at the airport, smoke from factories or

houses, dust, brush fires, and windmills.

Once a field has been selected, the student pilot should

always be required to indicate it to the instructor. Normally,

the student should be required to plan and fly

a pattern for landing on the field elected until the instructor

terminates the simulated emergency landing.

This will give the instructor an opportunity to explain

and correct any errors; it will also give the student an

opportunity to see the results of the errors.

However, if the student realizes during the approach

that a poor field has been selected—one that would

obviously result in disaster if a landing were to be

made—and there is a more advantageous field within

gliding distance, a change to the better field should

be permitted. The hazards involved in these last-minute

decisions, such as excessive maneuvering at very

low altitudes, should be thoroughly explained by the

instructor.

During all simulated emergency landings, the engine

should be kept warm and cleared. During a simulated

emergency landing, either the instructor or the student

should have complete control of the throttle. There

should be no doubt as to who has control since many

near accidents have occurred from such misunderstandings.

Every simulated emergency landing approach should

be terminated as soon as it can be determined whether

a safe landing could have been made. In no circumstances

should you violate the altitude restrictions

detailed in 14 CFR part 91 or any local nonaviation

regulations in force. It is also important to be courteous

to anyone on the ground. In no case should it be

continued to a point where it creates a hazard or an

annoyance to persons or property on the ground.

In addition to flying the powered parachute from the

point of simulated engine failure to where a reasonable

safe landing could be made, the pilot should also

learn certain emergency cockpit procedures. The habit

of performing these cockpit procedures should be developed

to such an extent that, when an engine failure

actually occurs, the pilot will check the critical items that would be necessary to get the engine operating

again after selecting a field and planning an approach.

Accomplishing emergency procedures and executing

the approach may be difficult for the pilot during the

early training in emergency landings.

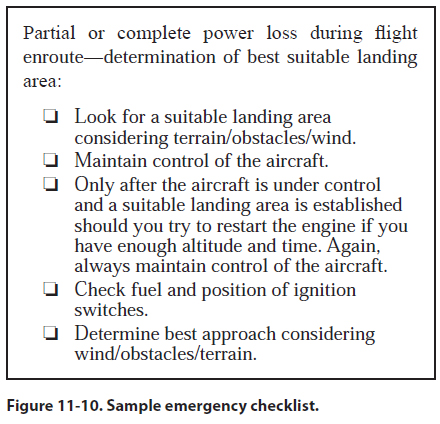

There are definite steps and procedures to follow in a

simulated emergency landing. They should be learned

thoroughly by the student, and each step called out

to the instructor. The use of a checklist is strongly

recommended. Most powered parachute manufacturers

provide a checklist of the appropriate items.

[Figure 11-10]

Critical items to be checked should include the quantity

of fuel in the tank and the position of the ignition

switches. Many actual emergency landings could have

been prevented if the pilots had developed the habit of

checking these critical items during flight training to

the extent that it carried over into later flying.

Instruction in emergency procedures should not be

limited to simulated emergency landings caused by

power failures. Other emergencies associated with

the operation of the powered parachute should be ex-plained, demonstrated, and practiced if practicable.

Among these emergencies are such occurrences as fire

in flight, electrical system malfunctions, unexpected

severe weather conditions, engine overheating, imminent

fuel exhaustion, and the emergency operation of

powered parachute systems and equipment.

|