|

Chapter 6 — Basic Flight Maneuvers

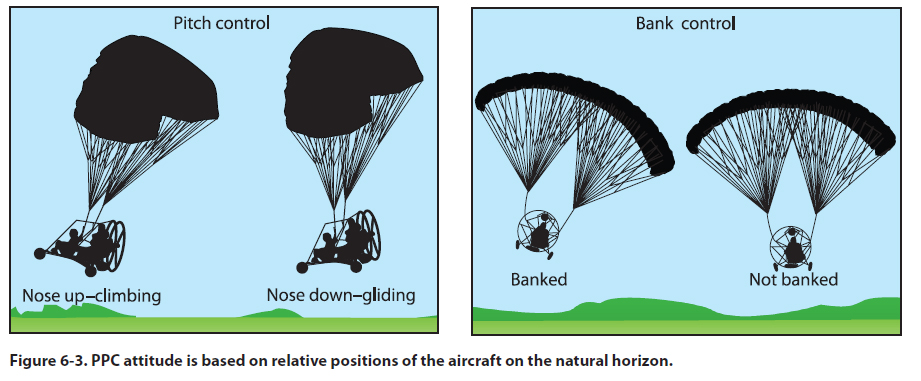

Attitude Flying

In a PPC, flying by attitude means visually establishing

the aircraft’s attitude with reference to the natural

horizon. [Figure 6-3] Attitude is the angular difference

measured between an aircraft’s axis and the line of the

Earth’s horizon. Pitch attitude is the angle formed by

the longitudinal axis of the aircraft and the horizon.

Bank attitude is the angle formed by the lateral axis

with the horizon.

In attitude flying, the PPC pilot controls two components:

pitch and bank.

• Pitch control is the control of the PPC about the

lateral axis by using the throttle to raise and

lower the nose in relation to the natural horizon.

• Bank control is control of the PPC about the

longitudinal axis by use of the PPC steering

controls to attain a desired bank angle in

relation to the natural horizon.

Straight-and-Level Flight

It is impossible to emphasize too strongly the necessity

for forming correct habits in flying straight and

level. All other flight maneuvers are in essence a deviation

from this fundamental flight maneuver. Perfection

in straight-and-level flight will not come of

itself. It is not uncommon to find a pilot whose basic

flying ability consistently falls just short of minimum

expected standards, and upon analyzing the reasons

for the shortcomings to discover that the cause is the

inability to properly fly straight and level.

Straight-and-level flight is flight in which a constant

heading and altitude are maintained. It is accomplished

by making immediate and measured corrections for

deviations in direction and altitude from unintentional

slight turns, descents, and climbs. Level flight, at first,

is a matter of consciously fixing the relationship of

the position of some portion of the PPC, used as a

reference point, with the horizon. In establishing the

reference points, place the PPC in the desired position

and select a reference point. No two pilots see

this relationship exactly the same. The references will

depend on where the pilot is sitting, the pilot’s height

(whether short or tall), and the pilot’s manner of sitting.

It is, therefore, important that during the fixing

of this relationship, you sit in a normal manner; otherwise

the points will not be the same when the normal

position is resumed.

In learning to control the aircraft in level flight, it is

important to use only slight control movements, just

enough to produce the desired result. Pilots need to

associate the apparent movement of the references

with the forces which produce it. In this way, you can

develop the ability to regulate the change desired in

the aircraft’s attitude by the amount and direction of

forces applied to the controls.

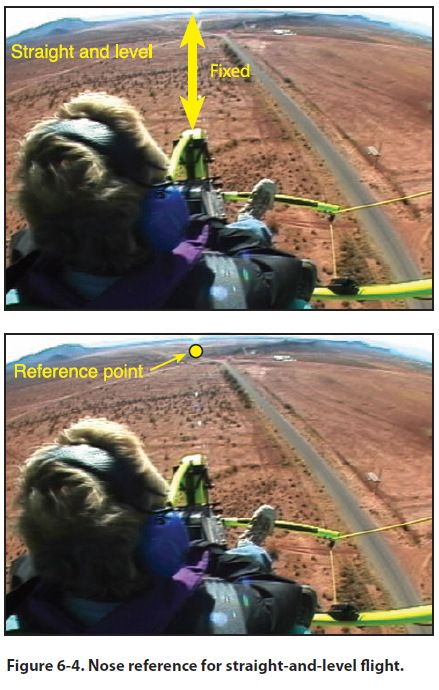

The pitch attitude for level flight (constant altitude) is

usually obtained by selecting some portion of the aircraft’s

nose as a reference point, and then keeping that

point in a fixed position relative to the horizon. [Figure

6-4] Using the principles of attitude flying, that position

should be cross-checked occasionally against the

altimeter (if so equipped) to determine whether or not

the pitch attitude is correct. If altitude is being gained

or lost, the pitch attitude should be readjusted in relation

to the horizon and then the altimeter rechecked to determine if altitude is now being maintained. The application

of increasing and decreasing throttle is used

to control this attitude.

In all normal maneuvers, the term “increase the pitch

attitude” implies raising the nose in relation to the horizon

(by increasing power); the term “decreasing the

pitch attitude” means lowering the nose (by decreas- ing power). While foot controls do have an effect on

altitude, they are not typically used as a control for

flying straight and level. A PPC must be capable of

maintaining altitude to tolerances using the controls

as designed.

Anytime the wing is banked, even very slightly, the

aircraft will turn. In a PPC the pilot has no useful

reference to measure bank angle like an airplane or

weight shift control aircraft where the wing tips are

visible in relation to the horizon. The objective of

straight-and-level flight is to detect small deviations

from laterally level flight as soon as they occur, necessitating

only small corrections. Reference to the magnetic

compass or GPS, if so equipped, can be made

to note any change in direction; however, the visual

reference of a point on the horizon with a point on the

aircraft such as the front wheel or instrument panel

will typically be used for sport pilot training.

Continually observing the nose to align the heading

should be avoided. The pilot must spend more time

scanning for air traffic than focusing on heading. This

helps divert the pilot’s attention from the aircraft’s

nose, prevents a fixed stare, and automatically expands

the pilot’s area of vision by increasing the range

necessary for the pilot’s vision to cover.

Straight-and-level flight requires almost no application

of control pressures if the aircraft is properly

trimmed to fly straight and the air is smooth. Some

PPCs will have a directional trim control which adjusts

the tension in a control line to make it fly straight.

Each PPC manufacturer has a unique design for their

particular aircraft. The pilot must not form the habit

of constantly moving the controls unnecessarily. You

must learn to recognize when corrections are necessary,

and then make a measured response. Tolerances

necessary for passing the PPC practical test are ±10

degrees heading and ±100 feet altitude. Students may

initially start to make corrections when tolerances are

exceeded but should strive to initiate a correction before

the tolerances are exceeded, such as starting correction

before the tolerance is ±5 degreees heading

and ±50 feet altitude.

Since the PPC does not have an elevator to control the

pitch, immediate minor adjustments should be made

while flying close to the ground. In flying a low approach

(flying straight and level over the centerline of

the runway at a low but specified distance from the

ground), think of the throttle as the coarse and slow

response altitude control, and application of both

steering controls (flare) as the fine adjustments to altitude adjustment. Throttle has a slight delay between

implementation and response in increasing altitude;

flare relatively quickly increases altitude but can only

hold altitude changes temporarily (about 2 seconds).

This would be like applying flaps on an airplane if no

elevator control was available.

While trying to maintain a constant altitude, especially

when close to the ground, you can fly with about onethird

flare. By holding a small flare, if you encounter

downdrafts, you can immediately add a large portion

of flare to lift you back to the desired altitude. If the

PPC begins to climb, then you can reduce the amount

of the flare to return to the desired altitude, until you

can adjust your throttle position again.

Common errors in the performance of straight-andlevel

flight are:

• Attempting to use improper reference points on

the aircraft to establish attitude.

• Forgetting the location of preselected reference

points on subsequent flights.

• Attempting to establish or correct aircraft

attitude using flight instruments rather than

outside visual reference.

• Overcontrol and lack of feel.

• Improper scanning and/or devoting insufficient

time to outside visual reference.

• Fixation on the nose (pitch attitude) reference

point.

• Unnecessary or inappropriate control inputs.

• Failure to make timely and measured control

inputs when deviations from straight-and-level

flight are detected.

• Inadequate attention to sensory inputs in

developing feel for the PPC.

|