Chapter 5

COMPONENT COMPATIBILITY

Once the rigger has all of the current manuals and information,

the inspection can continue. This covers not just

the canopy but also the entire assembly. In addition to

looking for damage or contamination to the system, the

rigger must make sure that all of the component parts are

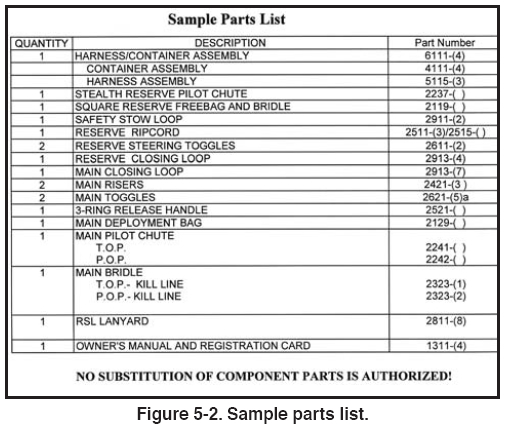

compatible and approved by the manufacturer. Figure 5-2 shows a sample parts list for a typical sport parachute,

having dual parachutes in a single harness system (a piggyback).

This parts list delineates exactly what parts are

used in the assembly of the system. The rigger should

check each component part and its identifying label or

stamp against the parts list. Mismatched component parts

are among the most frequent problems found in the field.

Many riggers are under the impression they can freely

interchange component parts, but this may be done only

within certain limits. Paragraph 11(a) of Advisory

Circular (AC) 105-2C, Sport Parachute Jumping, states:

“The assembly or mating of approved parachute components

from different manufacturers may be made by a certificated

and appropriately rated parachute rigger or

parachute loft in accordance with the parachute manufacturer’s

instructions and without further authorization by

the manufacturer or the FAA. Specifically, when various

parachute components are interchanged, the parachute

rigger should follow the canopy manufacturer’s instructions

as well as the parachute container manufacturer’s

instructions. However, the container manufacturer’s

instructions take precedence when there is a conflict

between the two.” In figure 5-2, note the bold print at the

bottom of the page: “NO SUBSTITUTION OF COMPONENT

PARTS IS AUTHORIZED!” This manufacturer

specifically states that you cannot use anything other than

Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) parts.

Substituting other parts places the rigger in violation of

the Code of Federal Regulations.

A common problem found in the field concerns reserve

ripcords. Several manufacturers of sport rigs use a onepin

ripcord with a mini trapezoidal handle and a cable

length 27-29 inches long. Depending on the actual container

it goes into, it’s possible to use one manufacturer’s

ripcord in another container as long as the rigger feels

there is sufficient excess cable for safety reasons.

However, imagine one ripcord is 27 inches overall and is

used in a system that is approved under Technical

Standard Order (TSO) C-23b and is rated at 300 pounds.

Another ripcord is 28 inches overall and is used in a

system approved under TSO C-23c, and is rated at 600

pounds for use with a Reserve Static Line (RSL) installation.

The problem here is the mating of different TSO

standard components. Installing the first ripcord in the

second container with an RSL lanyard may be degrading

the safety aspect of the system. So how does the rigger

tell which is which? The ripcord approved under

TSO C-23b will have minimal markings, perhaps only a

manufacturer’s part number. The ripcord approved

under TSO C-23c will have several markings on the handle

as required by the TSO. It should have the manufacturer’s

part number, manufacturer’s identification,

TSO-C23c, and the batch or serial number or date of

manufacture. [Figure 5-3] In reality, as long as the cable

lengths are compatible, the function of the ripcord will

probably work. The problem surfaces in the event of a

problem or incident involving the system. At this point,

the FAA could find the mismatched component and take

action against the rigger who packed the parachute.

A bigger problem surfaces when the rigger substitutes a

reserve deployment bag made by another manufacturer.

Most reserve deployment bags are compatible with the

appropriate container based on dimensions and volume.

If the deployment bag does not fit correctly, there can be

a problem with proper functioning of the system. These

are two examples of the more common compatibility

issues that are regularly found in the field. There are others

that the rigger may encounter and need to address as

well. The best solution is for the rigger to follow the manufacturer’s

parts list strictly to ensure the safety of the

parachute system.

After the rigger has determined that all of the component

parts are compatible, he/she can now commence the

actual inspection of the parachute assembly. Figure 5-4

shows a typical pilot emergency parachute assembly with

a round canopy laid out on the packing table. Make sure

the canopy is straight and the apex lines are even. Then

apply firm tension to the canopy and lines using a tension

board. The standard is to start at the top of the assembly.

This assembly in figure 5-4 can be broken down into six

separate areas. They are:

1. Pilot chute and bridle.

2. Canopy and deployment device.

3. Suspension lines and connector links.

4. Container.

5. Harness including risers.

6. Ripcord.

Inspection/packing checklists allow riggers to track their

progress as they do their inspection. [Figure 5-5] It is

desirable for riggers to complete their inspection uninterrupted,

which ensures that the inspection process is

followed and nothing gets overlooked. This rarely happens,

however, due to normal interruptions such as phone

calls or customer questions. Using the inspection checklist

ensures that after an interruption, the rigger is able to continue at the proper spot without missing anything.

This checklist is divided into seven sections that make it

usable for all types of parachute assemblies. It includes

an area for counting the tools at the beginning and end of

the inspection and packing procedure. This ensures that

no tools are overlooked or left in the parachute. While this

may sound implausible to some, it has happened over the

years, sometimes with fatal consequences.

|