|

AvStop Magazine Online Reconnaissance and the Cuban Missile Crisis |

||

|

Probably at no time in this nation's history has the importance of aerial reconnaissance been demonstrated more dramatically than during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. In September and October of that year, Soviet officials had persistently denied their intent to install offensive weapons in Cuba, only 90 miles from U.S. shores, despite intelligence reports to the contrary. On Oct. 14, two USAF high-flying U-2 reconnaissance aircraft photographed portions of Cuba and analysis of these photos confirmed that bases were being constructed for intermediate-range missiles within striking distance of the United States. President John F. Kennedy placed the U.S. armed forces on alert for whatever action might be necessary as USAF U-2 and RF-101 flights over Cuba continued, the latter aircraft sometimes flying at tree-top level. |

|

|

| On Oct. 22, President Kennedy publicly announced details of the critical situation and declared that "...a strict quarantine on all offensive military equipment under shipment to Cuba is being initiated." Meanwhile, USAF aircraft kept the island of Cuba as well as the Caribbean and Atlantic Ocean areas under constant surveillance, providing the U.S. Navy with data on scores of ships at sea apparently enroute to Cuba. | ||

|

This photo was President Kennedy's favorite of all those taken during the Cuban crisis. It was taken with the camera displayed here on November 10, 1962 (from less than 500 ft. altitude at a speed of 713 mph). Clearly shown are Soviet-built SA-2 surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) in place at launch sites. These defensive missiles protected offensive weapons sites and posed a serious threat to U.S. reconnaissance aircraft. A copy of this portion of the strip photo was mounted in the President's office. The U-2 was designed and built for surveillance missions in the thin atmosphere above 55,000 feet. An unusual single-engine aircraft with sailplane-like wings, it was the product of a team headed by Clarence L. "Kelly" Johnson at Lockheed's "Skunk Works" in Burbank, California. The U-2 made its first flight in August 1955 and began operational service in 1956. Its employment was kept secret until May 1, 1960, when a civilian-piloted U-2 was downed on a non-USAF reconnaissance flight over Soviet territory. USAF U-2s have been used for various missions. On October 14, 1962, Maj. Richard S. Heyser piloted a U-2 over Cuba to obtain the first photos of Soviet offensive missile sites. |

|

|

Maj. Rudolph Anderson, Jr. was killed on a similar mission eight days later when his U-2 was shot down. U-2s also have been used in mapping studies, atmospheric sampling and for collecting crop and land management photographic data for the Department of Energy. The aircraft on display is the last U-2A built. During the 1960's it made 285 flights to gather data on high-altitude clear air-turbulence. In the 1970's it was used to flight-test reconnaissance systems. It was delivered to the Museum in May 1980, and is painted as a typical reconnaissance U-2. SPECIFICATIONS: Span: 80 ft., Length: 49 ft. 7 in., Height: 13 ft., Weight: 15,850 lbs. (17,270 lbs. with external fuel tanks), Armament: None, Engine: Pratt & Whitney J57-P-37A of 11,000 lbs. thrust (J75-P-13 of 17,000 lbs. thrust for later, models). PERFORMANCE: Maximum speed: 494 mph. Cruising speed: 460 mph., Range: 2,220 miles (over 3,000 miles for later models) Service Ceiling: Above 55,000 ft. (above 70,000 ft. for later models) On Oct. 28th, Soviet Premier Khrushchev agreed to remove the offensive missiles as well as the medium range twin-jet Il-28 "Beagle" bombers being assembled in Cuba. USAF reconnaissance aircraft then monitored Communist compliance with the agreement to remove this threat to our security. Viewed with a stereoscopic projector, the features have a three-dimensional effect. The pattern of dots surrounding several launch sites are actually camouflage nets which were intended to conceal the equipment positioned beneath them, but which the strip camera rendered ineffective. |

||

|

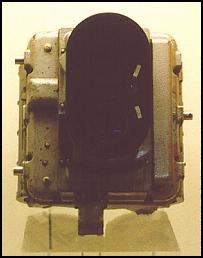

KA-18A Stereo Strip Camera This camera is one which was used during the series of reconnaissance flights over Cuba. Its design is unique in that it does not have a shutter which opens and closes, but instead operates on the principle of moving a strip of unexposed film past an open slit at a speed consistent with the apparent movement of the subject being photographed. This in reality, is the product of the camera being moved at a corresponding speed (such as in an airplane). The result is a camera which produces a continuous strip photo with sharp details generally unobtainable with shutter cameras mounted in aircraft flying at high speed at low altitude because of image blur caused by the aircraft's forward motion. Then-Colonel George W. Goddard had pioneered in the development of the strip camera just before WW II, basing his design on a newly-developed camera intended for use at race tracks to determine the winning horse in races which ended in a "Neck and Neck" finish. Difficulties in obtaining sharply-defined photos at low altitude during the Cuban Missile Crisis had prompted the USAF to consult with retired Brig. Gen. Goddard who immediately recommended the use of a strip camera, by then no longer regularly used by the USAF. Several KA-18A cameras were found in storage at Wright-Patterson AFB and on the night of Nov. 2-3, 1962, modifications were made to an RF-101C "Voodoo" and this camera was installed. On Nov. 10, photos were taken of Cuban missile installations with this camera and within 24 hours, they were being examined by President Kennedy. |

|

|