United States Women's Army Auxiliary Corps Is Created

|

Update: World War II was the largest and most violent armed conflict in the history of mankind. However, the half century that now separates us from that conflict has exacted its toll on our collective knowledge. While World War II continues to absorb the interest of military scholars and historians, as well as its veterans, a generation of Americans has grown to maturity largely unaware of the political, social, and military implications of a war that, more than any other, united us as a people with a common purpose. Highly relevant today, World War II has much to teach us, not only about the profession of arms, but also about military preparedness, global strategy, and combined operations in the coalition war against fascism. During the next several years, the U.S. Army will participate in the nation's 50th anniversary commemoration of World War II. The commemoration will include the publication of various materials to help educate Americans about that war. The works produced will provide great opportunities to learn about and renew pride in an Army that fought so magnificently in what has been called "the mighty endeavor." World War II was waged on land, on sea, and in the air over several diverse theaters of operation for approximately six years. The following essay on the critical support role of the Women's Army Corps supplements a series of studies on the Army's campaigns of that war. This brochure was prepared in the U.S. Army Center of Military History by Judith A. Bellafaire. I hope this absorbing account of that period will enhance your appreciation of American achievements during World War II. The Women's Army Corps in World War II, Over 150,000 American women served in the Women's Army Corps (WAC) during World War 11. Members of the WAC were the first women other than nurses to serve within the ranks of the United States Army. Both the Army and the American public initially had difficulty accepting the concept of women in uniform. However, political and military leaders, faced with fighting a two-front war and supplying men and materiel for that war while continuing to send lend-lease material to the Allies, realized that women could supply the additional resources so desperately needed in the military and industrial sectors. Given the opportunity to make a major contribution to the national war effort, women seized it. By the end of the war their contributions would be widely heralded. The Women 's Army Auxiliary Corps, Early in 1941 Congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers of Massachusetts met with General George C. Marshall, the Army's Chief of Staff, and informed him that she intended to introduce a bill to establish an Army women's corps, separate and distinct from the existing Army Nurse Corps. Rogers remembered the female civilians who had worked overseas with the Army under contract and as volunteers during World War I as communications specialists and dietitians. Because these women had served the Army without benefit of official status, they had to obtain their own food and quarters, and they received no legal protection or medical care. Upon their return home they were not entitled to the disability benefits or pensions available to U.S. military veterans. Rogers was determined that if women were to serve again with the Army in a wartime theater they would receive the same legal protection and benefits as their male counterparts. As public sentiment increasingly favored the creation of some form of a women's corps, Army leaders decided to work with Rogers to devise and sponsor an organization that would constitute the least threat to the Army's existing culture. Although Rogers believed the women's corps should be a part of the Army so that women would receive equal pay, pension, and disability benefits, the Army did not want to accept women directly into its ranks. The final bill represented a compromise between the two sides. The Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) was established to work with the Army, "for the purpose of making available to the national defense the knowledge, skill, and special training of the women of the nation." The Army would provide up to 150,000 "auxiliaries" with food, uniforms, living quarters, pay, and medical care. Women officers would not be allowed to command men. The Director of the WAAC was assigned the rank of major. WAAC first, second, and third officers served as the equivalents of captains and lieutenants in the Regular Army, but received less pay than their male counterparts of similar rank. For example, although the duties of a WAAC first officer were comparable to those of a male captain, she received pay equivalent to that of a male first lieutenant. Enlisted women, referred to as "auxiliaries," were ranked in descending order from chief leader, a position comparable to master sergeant in the Regular Army, through junior leader, comparable to corporal, and down to auxiliary, comparable to private. Although the compromise WAAC bill did not prohibit auxiliaries from serving overseas, it failed to provide them with the overseas pay, government life insurance, veterans medical coverage, and death benefits granted Regular Army soldiers. If WAACs were captured, they had no protection under existing international agreements covering prisoners of war. Rogers' purpose in introducing the WAAC bill had been to obtain pay, benefits, and protection for women working with the military. While she achieved some of her goals, many compromises had been necessary to get the bill onto the floor. Rogers introduced her bill in Congress in May 1941, but it failed to receive serious consideration until after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December. General Marshall's active support and congressional testimony helped the Rogers bill through Congress. Marshall believed that the two-front war in which the United States was engaged would cause an eventual manpower shortage. The Army could ill afford to spend the time and money necessary to train men in essential service skills such as typing and switchboard operations when highly skilled women were already available. Marshall and others felt that women were inherently suited to certain critical communications jobs which, while repetitious, demanded high levels of manual dexterity. They believed that men tended to become impatient with such jobs and might make careless mistakes which could be costly during war. Congressional opposition to the bill centered around southern congressmen. With women in the armed services, one representative asked, "Who will then do the cooking, the washing, the mending, the humble homey tasks to which every woman has devoted herself; who will nurture the children?" After a long and acrimonious debate which filled ninety-eight columns in the Congressional Record, the bill finally passed the House 249 to 86. The Senate approved the bill 38 to 27 on 14 May. When President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the bill into law the next day, he set a recruitment goal of 25,000 for the first year. WAAC recruiting topped that goal by November, at which point Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson authorized WAAC enrollment at 150,000, the original ceiling set by Congress. The day the bill became law, Stimson appointed Oveta Culp Hobby as Director of the WAAC. As chief of the Women's Interest Section in the Public Relations Bureau at the War Department, Hobby had helped shepherd the WAAC bill through Congress. She had impressed both the media and the public when she testified in favor of the WAAC bill in January. In the words of the Washington Times Herald, "Mrs. Hobby has proved that a competent, efficient woman who works longer days than the sun does not need to look like the popular idea of a competent, efficient woman." Prior to her arrival in Washington, Hobby had had ten years' experience as editor of a Houston newspaper. The wife of former Texas Governor William P. Hobby, Oveta Culp Hobby was well versed in national and local politics. Before her marriage she had spent five years as a parliamentarian of the Texas legislature and had written a book on parliamentary procedure. Oveta Culp Hobby was thus the perfect choice for Director of the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps. The position needed a woman with a proven record of achievement. The individual selected had to be politically astute, with an understanding of how things got done in Washington and in the War Department. Most important, the Director of the WAAC had to show a skeptical American public that a woman could be "a lady" and serve as a member of the armed forces at the same time. This was crucial to the success of the WAAC. A volunteer force, the WAAC had to appeal to small town and middle-class America to recruit the skilled clerical workers, teachers, stenographers, and telephone operators needed by the Army. The values and sensibilities of this middle class were very narrow, as exemplified by the words of Charity Adams, a WAAC officer candidate and later lieutenant colonel: "I made a conscientious effort to obtain every item on the list of suggested supplies for training camp except the slacks and shorts. I had never owned either, feeling that I was not the type to wear them." In small town America in 1942, ladies did not wear slacks or shorts in public. Initially, Major Hobby and the WAAC captured the fancy of press and public alike. William Hobby was quoted again and again when he joked, "My wife has so many ideas, some of them have got to be good!" Hobby handled her first press conference with typical aplomb. Although the press concentrated on such frivolous questions as whether WAACs would be allowed to wear makeup and date officers, Hobby diffused most such questions with calm sensibility. Only one statement by the Director caused unfavorable comment. "Any member of the Corps who becomes pregnant will receive an immediate discharge," said Hobby. The Times Herald claimed that the birth rate would be adversely affected if corps members were discouraged from having babies. "This will hurt us twenty years from now," said the newspaper, "when we get ready to fight the next war." Several newspapers picked up this theme, which briefly caused much debate among columnists across the nation. Oveta Culp Hobby believed very strongly in the idea behind the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps. Every auxiliary who enlisted in the corps would be trained in a noncombatant military job and thus "free a man for combat." In this way American women could make an individual and significant contribution to the war effort. Hobby's sincerity aided her in presenting this concept to the public. In frequent public speeches, she explained, "The gaps our women will fill are in those noncombatant jobs where women's hands and women's hearts fit naturally. WAACs will do the same type of work which women do in civilian life. They will bear the same relation to men of the Army that they bear to the men of the civilian organizations in which they work." In Hobby's view, WAACs were to help the Army win the war, just as women had always helped men achieve success. WAAC officers and auxiliaries alike accepted and enlisted under this philosophy. A WAAC recruit undergoing training at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia, whose husband was serving in the Pacific, wrote her friend, "The WAAC mission is the same old women's mission, to hold the home front steadfast, and send men to battle warmed and fed and comforted; to stand by and do dull routine work while the men are gone." Recruitment and Training, Major Hobby immediately began organizing the WAAC recruiting drive and training centers. Fort Des Moines, Iowa, was selected as the site of the first WAAC training center. Applications for the WAAC officer training program were made available at Army recruiting stations on 27 May, with a return deadline of 4 June. Applicants had to be U.S. citizens between the ages of 21 and 45 with no dependents, be at least five feet tall, and weigh 100 pounds or more. Over 35,000 women from all over the country applied for less than 1,000 anticipated positions. On 20 July the first officer candidate training class of 440 women started a six-week course at Fort Des Moines. Interviews conducted by an eager press revealed that the average officer candidate was 25 years old, had attended college, and was working as an office administrator, executive secretary, or teacher. One out of every five had enlisted because a male member of her family was in the armed forces and she wanted to help him get home sooner. Several were combat widows of Pearl Harbor and Bataan. One woman enlisted because her son, of fighting age, had been injured in an automobile accident and was unable to serve. Another joined because there were no men of fighting age in her family. All of the women professed a desire to aid their country in time of need by "releasing a man for combat duty." The press was asked to leave Fort Des Moines after the first day so as not to interfere with the training. Although a few reporters were disgruntled because they were not allowed to "follow" a candidate through basic officer training, most left satisfied after having obtained interviews and photographs of WAACs in their new uniforms. Even the titillating question of the color of WAAC underwear (khaki) was answered for the folks back home. Letters the women wrote home were often published in local newspapers. |

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

The forty black women who entered the first WAAC officer candidate class were placed in a separate platoon. Although they attended classes and mess with the other officer candidates, post facilities such as service clubs, theaters, and beauty shops were segregated. Black officer candidates had backgrounds similar to those of white officer candidates. Almost 80 percent had attended college, and the majority had work experience as teachers and office workers.

In July Army recruiting centers were supplied with applications for volunteers to enlist in the WAAC as auxiliaries (enlisted women). The response, although not as dramatic as the officer candidate applications, was still gratifying. Those who had applied unsuccessfully for officer training and who had stated on their applications that they would be willing to come in as auxiliaries did not have to reapply. Women were told that after the initial group of officers had been trained, all other officer candidates would be selected from the ranks of the auxiliaries as the corps grew. The first auxiliary class started its four-week basic training at Fort Des Moines on 17 August. The average WAAC auxiliary was slightly younger than the officer candidates, with a high school education and less work experience. These women enlisted for the same reasons as the officer candidates. Many with family members in the armed forces believed that the men would come home sooner if women actively helped win the war and that the most efficient way a woman could help the war effort was to free a man for combat duty.

Although the first WAAC officer candidate class started its training before the enlisted class, the first enlisted WAACs entered training before their future officers graduated. Consequently, the first classes of both WAAC officer candidates and enlisted personnel were trained by male Regular Army officers. Col. Donald C. Faith was chosen to command the center. Faith's background as an educator and his interest in the psychology of military education rendered him well suited for his position.

Eventually and gradually WAAC officers took over the training of the rest of the corps. The majority of the newly trained WAAC officers, the first of whom finished their training on 29 August, were assigned to Fort Des Moines to conduct basic training. As officer classes continued to graduate throughout the fall of 1942, many were assigned to staff three new WAAC training centers in Daytona Beach, Florida; Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia; and Fort Devens, Massachusetts. Others accompanied WAAC companies sent to U.S. Army field installations across the country. Black officers were assigned to black auxiliary and officer candidate units at Fort Des Moines and Fort Devens.

WAACs on the Job, The first auxiliary units and their officers to reach the field went to Aircraft Warning Service (AWS) units. The U.S. Army Air Forces could not rely on volunteer civilians to man stations twenty-four hours a day.

Many AWS volunteers who fit the WAAC enlistment requirements joined the WAAC with the understanding that upon graduating from basic training they would be assigned to duty at their local AWS station. By October 1942 twenty-seven WAAC companies were active at AWS stations up and down the eastern seaboard. WAACs manned "filter boards," plotting and tracing the paths of every aircraft in the station area. Some filter boards had as many as twenty positions, each one filled with a WAAC wearing headphones and enduring endless boredom while waiting for the rare telephone calls reporting aircraft sightings.

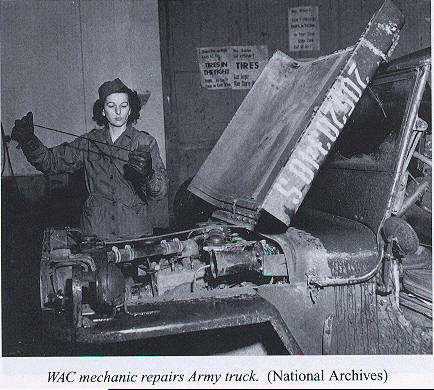

Later graduates were formed into companies and sent to Army Air Forces (AAF), Army Ground Forces (AGF), or Services of Supply (renamed Army Service Forces [ASF] in 1943) field installations. Initially most auxiliaries worked as file clerks, typists, stenographers, or motor pool drivers, but gradually each service discovered an increasing number of positions WAACs were capable of filling.

The AAF was especially anxious to obtain WAACs, and each unit was eagerly anticipated and very well treated. Eventually the Air Forces obtained 40 percent of all WAACs in the Army. Women were assigned as weather observers and forecasters, cryptographers, radio operators and repairmen, sheet metal workers, parachute riggers, link trainer instructors, bombsight maintenance specialists, aerial photograph analysts, and control tower operators. Over 1,000 WAACs ran the statistical control tabulating machines (the precursors of modern-day computers) used to keep track of personnel records. By January 1945 only 50 percent of AAF WACs held traditional assignments such as file clerk, typist, and stenographer.

A few AAF WAACs were assigned flying duties. Two WAAC radio operators assigned to Mitchel Field, New York, flew as crew members on B-17 training flights. WAAC mechanics and photographers also made regular flights. Three were awarded Air Medals, including one in India for her work in mapping "the Hump," the mountainous air route overflown by pilots ferrying lend-lease supplies to the Chinese Army. One woman died in the crash of an aerial broadcasting plane.

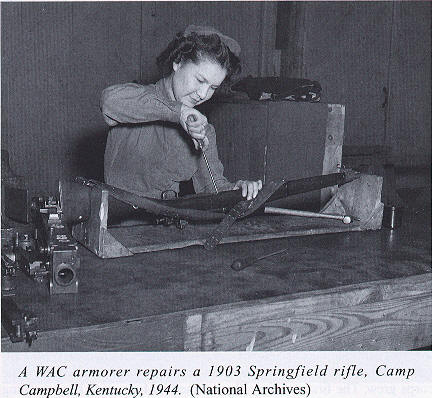

Army Service Forces received 40 percent of the WAACs. Some of the women assigned to the Ordnance Department computed the velocity of bullets, measured bomb fragments, mixed gunpowder, and loaded shells. Others worked as draftsmen, mechanics, and electricians, and some received training in ordnance engineering.

Many of the 3,600 WAACs assigned to the Transportation Corps (ASF) processed men for assignment overseas, handling personnel files and issuing weapons. In the words of one WAAC, "Soldiers come in here unarmed and leave with a gun. It gives me a pretty good feeling." WAACs served as boat dispatchers and classification specialists.

Later in the war, women were trained to replace men as radio operators on U.S. Army hospital ships. The Larkspur, the Charles A. Stafford, and the Blanche F. Sigman each received three enlisted women and one officer near the end of 1944. This experiment proved successful, and the assignment of female secretaries and clerical workers to hospital ships occurred soon after.

WAACs assigned to the Chemical Warfare Service (ASF) worked both in laboratories and in the field. Some women were trained as glass blowers and made test tubes for the Army's chemical laboratories. Others field tested equipment such as walkie-talkies and surveying and meteorology instruments.

The 250 WAACs assigned to the Quartermaster Corps (ASF) kept track of stockpiles of supplies scattered in depots across the country. Their duties included inspection, procurement, stock control, storage, fiscal oversight, and contract termination.

Over 1,200 WAACs assigned to the Signal Corps (ASF) worked as telephone switchboard operators, radio operators, telegraph operators, cryptologists, and photograph and map analysts. WAACs assigned as photographers received training in the principles of developing and printing photographs, repairing cameras, mixing emulsions, and finishing negatives. Women who became map analysts learned to assemble, mount, and interpret mosaic maps.

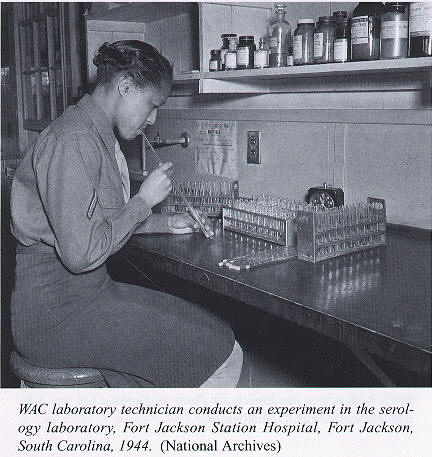

WAACs within the Army Medical Department (ASF) were used as laboratory, surgical, X-ray, and dental technicians as well as medical secretaries and ward clerks, freeing Army nurses for other duties.

Services of Supply, WAACs assigned to the Corps of Engineers participated in the Manhattan Project. M. Sgt. Elizabeth Wilson of the Chemistry Division at Los Alamos, New Mexico, ran the cyclotron, used in fundamental experiments in connection with the atomic bomb. WAAC Jane Heydorn trained as an electronics construction technician and, as part of the Electronic Laboratory Group at Los Alamos, was involved in the construction of the electronic equipment necessary to develop, test, and produce the atomic bomb. WAACs at the Oak Ridge, Tennessee, site maintained the top secret files related to the project, working twelve-hour shifts seven days a week. Other WAACs involved in the Manhattan Project included three women assigned to the Corps of Engineers in London, who helped to coordinate the flow of information between English and American scientists cooperating on the project.

The Army Ground Forces were initially reluctant to request and employ WAACs. The AGF eventually received 20 percent of all WAAC assignments. Many high-ranking staff officers would have preferred to see women aid the defense effort by taking positions in industry. A report prepared by the Plans Section, AGF, reflected this attitude: "In industry it is necessary to train personnel in only a single operation on the production line. Military duties require a versatility that is acquired only by long experience." As a result, WAACs assigned to Army Ground Forces often felt unwelcome and complained of the intensive discipline imposed upon them. Most AGF WAACs worked in training centers where 75 percent performed routine office work. Another 10 percent worked in motor pools. AGF WAACs found that chances for transfer and promotion were extremely limited, and many women served throughout the war at the posts to which they were initially assigned. The stories of Ground Forces WAACs contrasted sharply with those of women assigned to the Air and Service Forces, who were routinely sent to specialist schools and often transferred between stations.

Women's Army Corps members served worldwide-in North Africa, the Mediterranean, Europe, the Southwest Pacific, China, India, Burma, and the Middle East. Overseas assignments were highly coveted, even though the vast majority consisted of the clerical and communications jobs at which women were believed to be most efficient. Only the most highly qualified women received overseas assignments. Some women turned down the chance to attend Officer Candidate School in favor of an overseas assignment.

The invasion of North Africa was only five days old when, on 13 November 1942, Lt. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower asked that five WAAC officers, two of whom could speak French, be sent immediately to Allied Force Headquarters to serve as executive secretaries. The ship carrying Third Officers Martha Rogers, Mattie Pinette, Ruth Briggs, Alene Drezmal, and Louise Anderson was torpedoed en route from Great Britain to Algiers. A British destroyer plucked two of the women from the burning deck of their sinking ship. The other three escaped in a lifeboat. While adrift on the high seas, they saved several seamen by pulling them into the boat with them. Picked up by a destroyer, they were delivered to Algiers with no uniforms, clothing, or supplies. The women were greeted by anxious officers with gifts of oranges and toiletries.

These five women served on General Eisenhower's staff successively throughout the North African, Mediterranean, and European campaigns. In 1945 Eisenhower stated, "During the time I have had WACs under my command they have met every test and task assigned to them . . . their contributions in efficiency, skill, spirit and determination are immeasurable."

The first WAAC unit overseas, the 149th Post Headquarters Company, reported on 27 January 1943 to General Eisenhower's headquarters in Algiers. Initially unit members were housed in the dormitory of a convent school and transported to and from the headquarters in trucks. They served as postal workers, clerks, typists, and switchboard operators. Nightly bombings and accompanying antiaircraft fire made sleep difficult for the first few weeks, but most of the women acclimated fairly quickly. Additional WAAC postal workers joined them in May. A WAAC signal company arrived in November to take jobs as high-speed radio operators, teletypists, cryptographic code clerks, and tape cutters in radio rooms. Corps members assigned to the Army Air Forces arrived in North Africa in November 1943 and January 1944.

One of the most famous WAAC/WAC units to serve in the North African and Mediterranean theaters was the 6669th Headquarters Platoon, assigned to Lt. Gen. Mark W. Clark's Fifth Army. This unit became the Army's "experiment" in the use of female units in the field. The 6669th accompanied Fifth Army headquarters from Mostaganem, Algeria, across the Mediterranean to Naples and eventually all the way up the boot of Italy. Unit members remained from six to thirteen miles behind the front lines, moved with the headquarters group, and worked in traditional female skills. The unit's table of organization called for 10 telephone operators, 7 clerks, 16 clerk-typists, 10 stenographers, and 1 administrative clerk. Even so, these jobs had a vastly different flavor from traditional employment in the United States. WAAC telephone operators were required to get through extremely complicated communications networks to reach within minutes the commanding officer of any unit sought by General Clark. Clerk-typists plotted the locations and movements of the troops and requisitioned and tracked the delivery of crucial supplies. Clark and his staff treated the WAACs as valued members of the Fifth Army team, and the women responded by submitting to the hardships associated with forward troop movements with little complaint.

The WAACs' success in the North African and Mediterranean theaters led to an increasing number of requests for WAACs from overseas theaters. Before the War Department could honor these requests, however, it had to find a solution to a more immediate problem. In early 1943 the number of women joining the WAAC dropped drastically due to a sudden backlash of public opinion against the employment of women in the armed forces.

Unfortunately, a variety of social factors had combined to produce a negative public image of the female soldier. Letters home from enlisted men contained a great deal of criticism of female soldiers. When the Office of Censorship ran a sample tabulation, it discovered that 84 percent of soldiers' letters mentioning the WAAC were unfavorable.

Many of these soldiers had never seen a WAAC. But they were away from home and facing unknown dangers, and many kept up their spirits by imagining their return to the family and community they had left behind. It was important that the family and community remain unchanged. Women in the military represented change.

Enlisted soldiers tended to question the moral values of any woman attracted to military service and passed these beliefs on to their families at home. Many soldiers believed that the WAACs' duties included keeping up morale and "keeping the men happy." To this end, contraceptives were supposedly issued to all WAACs, and large numbers of pregnant WAACs were being returned home from overseas. It was rumored that 90 percent of the WAACs were prostitutes and that 40 percent of all WAACs were pregnant. According to one story, any soldier seen dating a WAAC would be seized by Army authorities and provided with medical treatment.

Given this "traditional male folklore," the early WAAC slogan, "Release a Man for Combat," was an unfortunate choice. Due to supposed sexual overtones, the slogan was changed to "Replace a Man for Combat," but the modification made little difference. Concerned soldiers believed that WAACs were not fit company for their sisters and girlfriends, and many forbade their wives, fiancees, and sisters to join the WAAC, some even threatening divorce or disinheritance. After American servicemen saw WAACs on the job and worked with them, many changed their minds. But by then the damage had already been done.

Another source of adverse public opinion regarding the WAAC took root in cities and towns adjoining military bases. Scurrilous rumors were sometimes started by jealous civilian workers who feared that their jobs were endangered by the arrival of WAACs, or by townspeople annoyed at WAACs who came to town in groups and "took over" favorite restaurants and beauty shops. The growth of many Army posts during this period changed many small communities forever, and the presence of women in uniform for the first time typified these changes.

The most significant cause of anti-WAAC feelings originated with the many enlisted soldiers who, comfortable in their stateside jobs, did not necessarily want to be "freed" for combat. The mothers, wives, sisters, and fiancees of these men were not anxious to see them sent into combat either, and many people believed the WAACs were to blame for this possibility. Such people often found it convenient to believe the worst rumors about female soldiers and sometimes repeated such gossip to their friends and neighbors.

In general, the American press had reported favorably, if rather frivolously, on the WAAC. Although editors devoted an inordinate amount of space to the color of WAAC underwear and the dating question, the press was usually sympathetic to the adjustments made by women to military life and the exciting job and travel opportunities awaiting those who enlisted.

However, there were exceptions. In the well-known column, "Capitol Stuff," carried nationwide by the McCormick newspaper chain, columnist John O'Donnell claimed that a "super-secret War Department policy authorized the issuance of prophylactics to all WAACs before they were sent overseas." O'Donnell insisted that WAAC Director Oveta Culp Hobby was fully aware of and in agreement with this policy. The entire charge was, of course, a fabrication, and O'Donnell was forced to retract his allegation.

The damage done to the WAAC by this column, even with the rapid retraction, was incalculable. WAACs and their relatives were outraged and humiliated. The immediate denials issued by President and Mrs. Roosevelt, Secretary Stimson, and Lt. Gen. Brehon B. Somervell of the Army Service Forces mitigated the feelings of some but did little to alleviate the shock of many. The inevitable general public discussion led Congress to summon Director Hobby to produce statistics on WAAC pregnancies and the frequency of venereal disease. Upon learning of the exceptionally small percent cited, Congress commended Major Hobby and the WAAC.

The Women 's Army Corps, While press and public discussed the merits of the WAAC, Congress opened hearings in March 1943 on the conversion of the WAAC into the Regular Army. Army leaders asked for the authority to convert the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps into the Women's Army Corps (WAC), which would be part of the Army itself rather than merely serving with it. The WAAC had been an unqualified success, and the Army received more requests for WAACs than it could provide. Although WAACs were desperately needed overseas, the Army could not offer them the protection if captured or benefits if injured which Regular Army soldiers received. The plans for an eventual Allied front in Europe required a substantially larger Army, with many more jobs that women could fill. Establishment of a Women's Army Corps with pay, privileges, and protection equal to that accorded to men was seen as a partial solution to the Army's problem.

On 3 July 1943, after a delay caused by congressional hearings on the slander issues, the WAC bill was signed into law. All WAACs were given a choice of joining the Army as a member of the WAC or returning to civilian life. Although the majority decided to enlist, 25 percent decided to leave the service at the time of conversion.

Women returned home for a variety of reasons. Some were needed at home because of family problems; others had taken a dislike to group living and Army discipline. Some women did not want to wear their uniform while off duty, as required of all members of the armed forces. Women electing to leave also complained that they had not been kept busy or that they had not felt needed in their jobs. Not surprisingly, the majority of those who left had been assigned to the Army Ground Forces, which had been reluctant to accept women in the first place and where the women were often underutilized and ignored. Some 34 percent of the WAACs allocated to the Army Ground Forces decided to leave the service at the time of conversion, compared to 20 percent of those in the Army Air Forces and 25 percent of those in the Army Service Forces.

With the conversion of the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps to the Women's Army Corps, former WAAC first, second, and third officers became captains and first and second lieutenants, respectively. Director Hobby was officially promoted to the rank of colonel; WAC service command and theater staff directors were promoted to lieutenant colonels. Company commanders became captains or majors depending upon the size of their command and their time in service. Enlisted women were ranked as master sergeant through corporal and private, the same as their male counterparts.

The conversion of the WAAC to the Women's Army Corps and the "image" controversy of 1943 combined to cause a crisis in WAC recruiting. In desperation, some WAC recruiters lowered the standards for acceptance into the corps, and a few even resorted to subterfuge to obtain the necessary numbers of recruits. In two southern states, recruiters haunted train and bus stations, waiting for women who came to send off husbands and fiancées to war. An Army recruiter would rush up after the soldier had departed and ask the unhappy woman if she wanted to do something to bring her man back sooner. When she answered "yes," the officer asked her to sign a paper. Many of the women thought they were signing a petition. Several days later, these women received notices to report for induction. They arrived at the training centers confused and angry, and many never adjusted to life in the WAC.

The War Department and the WAC leadership recognized the immediate need to step up the recruiting campaign to prevent these occurrences and to increase the number of enrollees who sincerely wanted to aid the war effort. The result was the All-States Campaign and the Job-Station Campaign. In the first, General Marshall asked state governors to assign committees of prominent citizens the task of recruiting statewide companies for the WAC, which would carry their state flags and wear their own state armbands while in training. In theory, state pride would encourage the committees to work diligently to fill their quotas. The Job-Station Campaign allowed recruiters to promise prospective enlistees their choice of duty and assignment location after they completed basic training. Both campaigns were successful, although they caused WAC administrators and training camp officials significant problems dealing with understrength and oversized state companies and with women who could dictate the terms of their assignments after they had completed basic training. Although WAC enlistments never reached the high levels attained early in the war, recruitment maintained a steady pace from the fall of 1943 through early 1945, allowing the War Department to respond to overseas theaters' requests with additional WAC companies.

The WAC Overseas, In July 1943 the first battalion of WACs to reach the European Theater of Operations (ETO) arrived in London. These 557 enlisted women and 19 officers were assigned to duty with the Eighth Air Force. A second battalion of WACs earmarked for Eighth Air Force reached London between 20 September and 18 October. The majority of these women worked as telephone switchboard operators, clerks, typists, secretaries, and motor pool drivers. WAC officers served as executive secretaries, cryptographers, and photo interpreters. The demand for switchboard operators and typists remained so high that in 1944 two classes of approximately forty-five women each were recruited within the theater and received three weeks of basic training in England.

A detachment of 300 WACs served with the Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). Originally stationed in Bushey Park, London, these WACs accompanied SHAEF to France and eventually to Germany. As stenographers, typists, translators, legal secretaries, cryptographers, telegraph and teletype operators, radiographers, and general clerks, these women assisted in the planning of D-day and all subsequent operations up to the defeat of Germany. WACs handled highly classified material, worked long hours with few days off, and were exposed to a significant amount of danger.

WAC stenographer Ruth Blanton, assigned to the G-2 (Intelligence) Section of SHAEF, held a typical assignment. Blanton's work consisted of recording and translating reports from the French underground. These reports were received from short-wave radio, decoded, and made available to those responsible for planning the invasion of France. The information detailed the number and location of bridges and railroad facilities sabotaged; the movements and strength of the German troops occupying France; and the activities of German officers. SHAEF staff members compiled files on individual German officers containing information on their education, family, hobbies, and length of service. Each morning Blanton typed the briefing reports the intelligence officers presented to the General Staff. During the afternoon she helped to bring the situation map up to date. This map covered one end of the G-2 office and showed Europe, Asia, and Africa. Battle lines were shown by map buttons listing the units engaged in each section and the enemy units opposing.

SHAEF WACs worked around the clock throughout the planning period for D-day. Plans were changed daily, and WACs typed both the critical changes and the alternate plans and routed them through the Allied command.

During this period the SHAEF compound located in Bushey Park near Kingston on the Thames River came under hostile fire. On 23 February 1944, an incendiary bomb struck the WAC area at Bushey Park, causing substantial damage to the WAC billets, mess hall, and company offices. As soon as the "all clear" sounded, WACs went to work putting out fires and soon had the area orderly and under control.

After D-day, 6 June 1944, German V-1 and V-2 missiles hit Bushey Park and London in increasing numbers. There was little defense against either the V-l, a pilotless aircraft traveling 400 miles an hour and falling to the ground when out of fuel, or the V-2 ballistic missile. On 3 July a V-l "buzz bomb" fell on the quarters of American soldiers and WACs in London. WACs administered first aid to injured soldiers, drove jeeploads of soldiers to the hospitals, and operated a mess in their own damaged building for civilian relief workers. The attacks stopped only after Allied ground forces cleared the German launch sites off the Cherbourg Peninsula.

On 14 July 1944, exactly one year after the first contingent of WACs landed in England and thirty-eight days after D-day, the first forty-nine WACs to arrive in France landed in Normandy. Assigned to the Forward Echelon, Communications Zone, they immediately took over switchboards recently vacated by the Germans and worked in tents, cellars, prefabricated huts, and switchboard trailers.

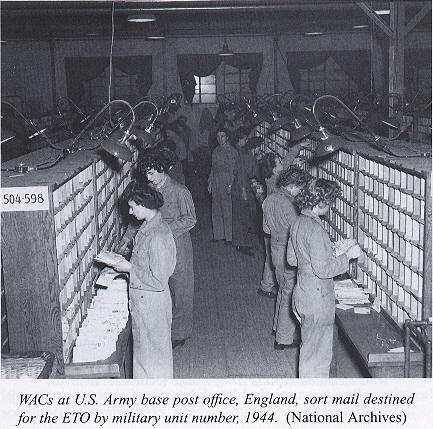

In February 1945 a battalion of black WACs received its long awaited overseas assignment. Organized as the 6888th Central Postal Battalion and commanded by Maj. (later Lt. Col.) Charity Adams, these 800 women were stationed in Birmingham, England, for three months, moved to Rouen, France, and finally settled in Paris. The battalion was responsible for the redirection of mail to all U.S. personnel in the European Theater of Operations (including Army, Navy, Marine Corps, civilians, and Red Cross workers), a total of over seven million people. When mail could not be delivered to the address on the face of the envelope, it was sent to the Postal Directory to be redirected. The 6888th kept an updated information card on each person in the theater. Some personnel at the front moved frequently, often requiring several information updates per month. The WACs worked three eight-hour shifts seven days a week to clear out the tremendous backlog of Christmas mail.

Each shift averaged 65,000 pieces of mail. Although the women's workload was heavy, their spirits were high because they realized how important their work was in keeping up morale at the front.

In general, WACs in the European theater, like those in the North African and Mediterranean theaters, held a limited range of job assignments: 35 percent worked as stenographers and typists, 26 percent were clerks, and 22 percent were in communications work. Only 8 percent were assigned jobs considered unusual for women: mechanics, draftsmen, interpreters, and weather observers. Some WACs were so anxious to serve overseas that they were willing to give up promotions and more interesting work assignments for the privilege. By V-E Day there were 7,600 WACs throughout the European theater stationed across England, France, and the German cities of Berlin, Frankfurt, Wiesbaden, and Heidelberg.

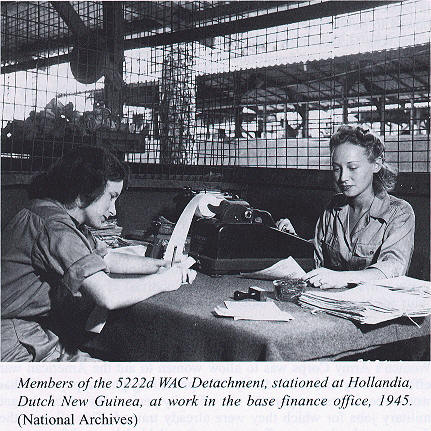

In the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA), the need for WACs became acute by mid-1944. WACs were stationed at Hollandia and Oro Bay, New Guinea, and at Leyte and Manila in the Philippines. Women who served in this theater faced numerous difficulties, only a few of which were inherent to the geographic area.

Because the Southwest Pacific Area Command was one of the last theaters to request and receive WACs, skilled office workers were scarce. Consequently the theater was sent numerous drivers and mechanics, many of whom were retrained on the spot as clerks and typists. Eventually 70 percent of the 5,500 WACs who served in the theater worked in administrative and office positions, 12 percent were in communications, 9 percent worked in stockrooms and supply depots, and 7 percent were assigned to motor transport pools.

The women learned that office work far behind the front lines was frequently crucial to the success of men in the field. T4g. Patricia Gibson was one of those who could see a direct relationship between her assignment and the war effort. Gibson prepared the loading requisitions for several vessels involved in successful amphibious landings against the Japanese at Morotai and Leyte. T. Sgt. Ethel Cahill was responsible for receiving and coordinating requests from the field forces for both personnel and equipment. Her carefully kept personnel records enabled her to promptly deploy properly trained and equipped personnel to combat forces as needed. WACs assigned to supply depots kept records which allowed them to send troops in the field the proper types and amounts of ammunition, motorized vehicles, and gasoline.

Many WAC officers worked as mail censors and became very skilled at this sensitive work. "Women seem to have an uncanny knack for discovering the tricky codes soldiers devise for telling their wives where they are," claimed the WAC officer's supervisor, reflecting the prevalent belief that men and women had different abilities. Censors on the job over a year became susceptible to depression because of the endless bitter complaints and reiterated obscenities in the majority of letters home. Supervisors suggested that women were "more sensitive than men by nature" and should not be given this type of work in the future.

Clothing requisitions posed severe problems in the SWPA. The WACs arrived in winter uniforms complete with ski pants and earmuffs (both of which would have been welcomed by the women in France) and heavy twill coveralls issued while en route. The coveralls proved too hot for the climate and many women developed skin diseases. The theater commander insisted the women wear trousers as protection against malaria-carrying mosquitoes, but the khaki trousers worn by the troops were scarce. Heat and humidity kept clothing wet from perspiration, and due to supply problems most women did not have enough clothing and shoes to allow laundered apparel the chance to dry before being worn again.

WACs in the SWPA had a highly restricted lifestyle. Fearing incidents between the women and the large number of male troops in the area, some of whom had not seen an American woman for eighteen months, the theater headquarters directed that WACs (as well as Army nurses) be locked within barbed-wire compounds at all times, except when escorted by armed guards to work or to some approved recreation. No leaves or passes were allowed. The women chafed under these restrictions, believing they were being treated like children or criminals. Male soldiers complained frequently in their letters home that WACs were not successfully "releasing men for combat" in the Southwest Pacific because it took so many GIs to guard them. The WACs in their turn resented the guards, believing them unnecessary and insulting.

After the WACs had been in the SWPA for approximately nine months, the number of evacuations for health reasons jumped from 98 per thousand to 267 per thousand, which was significantly higher than that for men. The high rate of WAC illness was directly related to the theater's supply problems. Among the leading causes of illness was dermatitis, a skin disease aggravated by heat, humidity, and the heavy winter clothing the WACs wore in the theater. The malaria rate for women was disproportionately high because WACs lacked the lightweight, yet protective clothing issued to the men and often failed to properly wear their heavier uniforms. Pneumonia and bronchitis were aggravated by a shortage of dry footgear.

Tropical custom imposed a lengthy working day on the WACs, with time off in the middle of the day to eat and rest. Many worked through the day, believing it was too hot during those hours to do either. Those who skipped meals often became run down.

Many women lost a significant amount of weight during their year's stay in the Pacific. Although the WACs performed well in the Southwest Pacific under daunting conditions, they did so at considerable personal cost. Regardless of the high incidence of illness, WAC morale remained high.

In July 1944, 400 WACs arrived in the China-Burma-India theater to serve with the Army Air Forces. Theater commander Lt. Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell had successfully blocked the employment of WACs in his theater prior to this time. He finally allowed Army Air Forces commander Maj. Gen. George E. Stratemeyer to obtain a contingent of WACs on the condition that they would serve only with his units. WACs assigned to these areas served as stenographers, typists, file clerks, and telephone and telegraph operators.

One month after V-E Day, 8 May 1945, WAC Director Oveta Culp Hobby resigned from the corps for personal reasons. Colonel Hobby's dedicated and skillful administration was the primary force behind the wartime success of the organization from its formation and overall philosophy through its rapid growth, the conversion from the WAAC to the WAC, and its accomplishments overseas. Hobby recommended as her successor Lt. Col. Westray Battle Boyce, Deputy Director of the WAC and former Staff Director of the North African Theater. Colonel Boyce was appointed WAC Director in July 1945 and oversaw the demobilization of the WAC after V-J Day in August 1945.

The Army acknowledged the contributions of the Women's Army Corps during World War II by granting numerous individual corps members various awards. WAC Director Oveta Culp Hobby received the Distinguished Service Medal. Sixty-two WACs received the Legion of Merit, awarded for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of duty. These awards went to WAC Deputy Director Lt. Col. Westray B. Boyce and the WAC staff directors of every theater of operations in which WACs were employed, as well as enlisted women such as Sgt. Maxine J. Rohkar, who received her award for "devotion to duty in administering classified documents pertaining to operations at Salerno and Anzio," and Sgt. Lettie F. Ewing, who "initiated and put into motion new methods of processing quartermaster requisitions."

Three WACs received the Air Medal, including Sgt. Henrietta Williams, assigned to an aerial reconnaissance mapping team in the China-Burma-India theater. Ten women received the Soldier's Medal for heroic actions (not involving combat). One such incident occurred at Port Moresby, New Guinea, when an oil stove in the women's barracks caught fire and three WACs brought the fire under control by smothering it, sustaining severe burns in the process. Sixteen women received the Purple Heart, awarded during World War II to soldiers injured due to enemy action. The majority of the WACs received their injuries from exploding V-l bombs while stationed in London. The Bronze Star was awarded to 565 women for meritorious service overseas. A total of 657 WACs received medals and citations at the end of the war.

Much of the Women's Army Corps was demobilized along with the rest of the Army starting immediately after V-E Day in Europe. Not all the women were allowed to return home immediately, however. In order to accomplish its occupation mission, the Army granted its commanders the authority to retain some specialists, including WACs, in place as long as they were needed. Within six months the Army bowed to public and political pressure and sent most of its soldiers home. On 31 December 1946, WAC strength was under 10,000, the majority of whom held stateside duty and who hoped to be allowed to stay in the Army.

Earlier in 1946, the Army asked Congress for the authority to establish the Women's Army Corps as a permanent part of the Regular Army. This is the greatest single indication of the success of the wartime WAC. The Army acknowledged a need for the skills society believed women could provide. Although the bill was delayed in Congress for two years by political conservatives, it finally became law on 12 June 1948. With the passage of this bill, the Women's Army Corps became a separate corps of the Regular Army. It remained part of the U.S. Army organization until 1978, when its existence as a separate corps was abolished and women were fully assimilated into all but the combat branches of the Army.

Conclusion, Ultimately, more than 150,000 American women served in the Army during World War II. The overall philosophy and purpose of the Women's Army Corps was to allow women to aid the American war effort directly and individually. The prevailing philosophy was that women could best support the war effort by performing noncombatant military jobs for which they were already trained. This allowed the Army to make the most efficient use of available labor and free men to perform essential combat duties.

The concept of women in uniform was difficult for American society of the 1940s to accept. In a 1939 Army staff study which addressed the probability that women would serve in some capacity with the Army, a male officer wrote that "women's probable jobs would include those of hostess, librarians, canteen clerks, cooks and waitresses, chauffeurs, messengers, and strolling minstrels." No mention was made in this report of the highly skilled office jobs which the majority of WACs eventually held, because such positions often carried with them significant responsibility and many people doubted that women were capable of handling such jobs.

Although women in key leadership roles both within and outside the government realized that American women were indeed capable of contributing substantially to the war effort, even they accepted the prevailing stereotypes which portrayed women as best suited for tasks which demanded precision, repetition, and attention to detail. These factors, coupled with the post-Depression fear that women in uniform might take jobs from civilians, limited the initial range of employment for the first wave of women in the Army.

Traditional restrictions on female employment in American society were broken during World War II by the critical labor shortage faced by all sectors of the economy. As "Rosie the Riveter" demonstrated her capabilities in previously male-dominated civilian industries, women in the Army broke the stereotypes which restricted them, moving into positions well outside of traditional roles. Overcoming slander and conservative reaction by many Americans, a phenomenon shared by their British and Canadian sisters in uniform, American women persisted in their service and significantly contributed to the war effort. The 1943 transition from auxiliary status to the Women's Army Corps was de facto recognition of their valuable service.

The Women's Army Corps was successful because its mission, to aid the United States in time of war, was part of a larger national effort that required selfless sacrifice from all Americans. The war effort initiated vast economic and social changes, and indelibly altered the role of women in American society.

| ©AvStop Online Magazine Contact Us Return To News |