Lessons From Aloha

by Martin Aubury

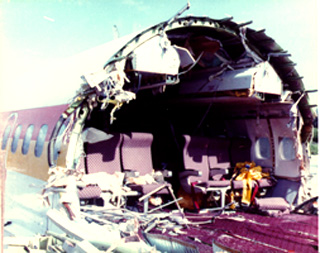

It is just four years since the amazing survival of a Boeing 737 which lost a large section of its fuselage over Hawaii. Only one person died, yet the accident galvanised the air transport industry to make monumental improvements. Ponder the lessons about complacency which have been learned from that accident. Aloha Airlines Flight 243 departed Hilo en route to Honolulu at 1.25 p.m. on 28 April 1988. As the Boeing 737 leveled off at top of its climb the fuselage ruptured and senior flight attendant Clarabelle Lansing was blown from the aircraft. To her death. The public hearing convened by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) two months later revealed just how complacent airlines and regulators had become. The factors which caused the accident were well known, some had been known for twenty years. It was just a matter of time before the factors came together and caused a tragedy. The Aloha Boeing was being flown by First Officer Madeline Tompkins when it burst apart. She told investigators how her head was jerked back by the blast. The Captain told how the cockpit door was blown away, how he could see back into the cabin and how there was blue sky where the roof had been. |

|

|

Back in the cabin, 89 passengers were strapped in but well aware of their plight. They had seen nearly six metres of cabin disappear, and some had seen Clarabelle Lansing swept through a hole in the left wall. The two other flight attendants had been standing in the aisle and were blown to the floor. One was seriously injured and a seated passenger had to hold on to her to keep her in the aircraft. The other attendant crawled along the aisle, clinging on to seat legs and comforting passengers. Not all of the structure had torn away cleanly. There were jagged bit of metal being battered by the slipstream, then breaking loose and spearing back among the passengers. Most of the passengers were injured, seven seriously. The crew diverted the crippled aircraft to nearby Maui. The Captain said that the aircraft was "shaking a little, rocking slightly, and felt springy." No doubt everyone on board was shaking. Experienced engineers still do not know how the aircraft held together and landed safely. The fuselage of the Aloha Boeing failed, despite the fact that it was designed and built to well proven rules. Why? A fuselage is designed to sustain all flight and landing loads and most importantly it must be strong enough to contain cabin air pressure. The skin is less than 1mm thick, the thickness of a credit card. It is made in panels which are typically about 4 metres long and 2 metres wide. |

|

These are joined together with rows of rivets. Obviously the skin is weaker where it is drilled for the rivets, so on early B737's Boeing engineers tried to reinforce the joints with epoxy adhesive. It was these joints which failed first and let the skins rip away from the aircraft. The first Boeing 737 was delivered in 1967, the Aloha aircraft was delivered in May 1969 and by about then Boeing became aware of problems with the adhesive bonding process. The adhesive worked much like a two tube mix used by a home handyman except that the glue was premixed and held on a scrim tape. By keeping it refrigerated the adhesive reaction was suspended. At the right time in construction the adhesive tape was laid between the skins, these were riveted together and the glue then cured as it warmed up to room temperature. That was the theory. In practice the adhesive did not really bond to the aluminum skin, it only bonded to the very thin layer of oxide on the surface of the aluminum. Attachment of the oxide film to the metal underneath was dangerously variable. Also if the scrim was too cold when it was applied it attracted condensation which prevented proper adhesion. If the scrim got too warm it partially cured before it was in place and again adhesion failed. Whenever adhesion failed the rivets and surrounding skin were overloaded and the skin began to crack. |

|

|

|

Boeing was not secretive about the problem. The bonding deficiencies and their rectification were discussed in many technical papers in the early 1970's. The whole U.S. industry was embarrassed because the Europeans had been successfully bonding aircraft for 30 years. In 1975 the U.S.A.F. stepped in with a large contract to catch up with the Europeans. It went to Boeing's arch rival, Douglas. Boeing progressively improved the design of the skin joints and hoped that for aircraft already in service the problem could be controlled with enhanced inspections. From May 1970 onwards Boeing sent the airlines a series of bulletins recommending inspection and sealing of the joints. Cracking and corrosion still went on. Diligent airlines found it and fixed it. Less diligent ones stayed lucky. After 17 years of increasing concern the U.S. regulatory authority, the Federal Aviation Administration (F.A.A.) issued a compulsory order, known as an Airworthiness Directive (A.D.) which required that all U.S. airlines inspect the skin joints on their old B737's. To keep costs down the F.A.A. only made the inspections mandatory along the two most critical joints. Inspection of the other joints was still at the discretion of each airline. John Mapel was the F.A.A. representative who had the job of ensuring that Aloha complied with aircraft maintenance requirements, including A.D.'s. His job title was Principle Maintenance Inspector and he had been assigned to Aloha for three years at the time of the accident. He told the accident enquiry that he had been concerned about maintenance practices at Aloha ever since he had gone there. F.A.A. has a surveillance program known as the National Aviation Safety Inspection Program (N.A.S.I.P.), which began because of widespread safety breaches engendered by deregulation. So Mapel instigated a N.A.S.I.P. audit of Aloha. It found problems, but they were related to paperwork and management rather than to the actual condition of the aircraft. Not much seems to have been done. Aloha people were still sure that their maintenance was good enough and Mapel still worried. |

Boeing too was concerned about maintenance of aging aircraft and had set up its own team to survey airlines when they were doing major work. Mr. Maple claims that due to his "nudging" Aloha invited the Boeing team to audit them. This happened in September 1987, October 1987 and January 1988. The Boeing people were thorough and had no doubt that Aloha and its aircraft were in trouble. But they would not tell F.A.A. or Mr Mapel. When the Boeing team met with Aloha executives to report its criticisms, Mr Mapel was excluded. He only heard of the meeting by chance and told the enquiry of the heated exchange which occurred when he tried to attend the crucial meeting. Apparently Boeing felt that if it passed any adverse findings to the regulatory authority it would lose the confidence of customer airlines and its own monitoring would be constrained. Boeing has since changed that view. It tells airlines to report adverse finding to their regulatory authority immediately, because Boeing will do so within 24 hours.

It seems that Aloha did listen to Boeing and had improvements in train but not soon enough to save Flight 243 and Clarabelle Lansing. Maintenance standards at Aloha were not abnormal. The whole industry had become complacent about maintenance and particularly about the durability of old aircraft. To put this in perspective the accident aircraft was nineteen years old, older no doubt than the cars driven by most of the passengers. The aircraft had operated for 35,496 hours, in other words it had actually been up in the air for a total of four years. The aircraft had taken off 89,680 times, that means each flight had averaged only about 25 minutes. Every 25 minutes the skin, the frames and the joints had been stretched as the fuselage had been pumped up to maximum pressure. How could the airlines and their mechanics have become complacent about their planes while treating them like this?

Although Boeing was concerned about its old aircraft in general terms, it too was complacent about the fuselage. This was because of a naive faith in a concept called the "lead crack". Boeing engineers believed that if the fuselage did crack anywhere, a single "lead crack" would grow along the skin until it reached a fuselage frame, then it would turn at right angles and a triangular shaped tear would blow out and safely dump fuselage pressure. Boeing is a close knit company and when an idea like this takes hold it becomes accepted as gospel. It went unchallenged by most of the FAA. The British and Australian authorities never accepted the concept but needed an accident to prove them right.

Amid the reams of evidence tabled at the enquiry is a letter from Australian fatigue experts questioning Boeing on the integrity of skin joints on their older B737's. The response from Boeing glibly assured that it had "demonstrated safe decompression in lap joints with a 32inch crack and verified multiple site damage in fastener holes". It is precisely this failure which crippled Flight 243. The Boeing letter was dated 14 April, just two weeks before the accident.

The alternative possibility which was feared by the Australians, was that small cracks would grow simultaneously at many nearby rivet holes. If this happened there would be little chance of finding the cracks by visual inspection, they would be too small or hidden by paint. And, when the cracks started to join up it could happen almost instantaneously. The debris left behind in the Aloha hull clearly showed that this had caused the accident.

The Aloha accident got dramatic media coverage around the world. In the U.S. it crystallized public concern about deteriorating safety standards in the aftermath of deregulation. The public and the media pressured Congress who, in turn pressured the F.A.A. If F.A.A would not take stringent action then the matter would be handled directly by Congress and all aircraft over a certain age would be banned.

Just five weeks after the accident the F.A.A. called an International Conference on Aging Airplanes. It was attended by 400 very concerned representatives from airlines, manufacturers and airworthiness authorities from 12 countries. In a keynote address, Jim Oberstar, Chairman of the Congressional Sub-Committee on Transport said:

"The purpose of this conference is

to apply the combined genius of experts from the three pillars of modern

aviation: the manufacturers, the carriers and the FAA to resolve yet another

vexing question for civil aviation: the problem of aging aircraft."

He went on to promise; "If more

inspectors and inspections are needed, Congress, I assure you, will provide

the funding, as we have done in the past" FAA field inspector staff had

sunk from 1672 to a low of 1331 in 1984. Since then, with the impetus of

Aloha and other accidents the number has doubled.

The conference set up an Airworthiness Assurance Task Force, led by Robert Doll, Vice President of Technical Services at United Airlines. Under it are three working groups; one reviewing the integrity of Boeing aircraft, one for Douglas aircraft and one for other transport aircraft (Lockheed and European). The very experienced, practical engineers in these groups quickly confirmed the extent of complacency which had set in throughout the industry. The problems were not limited to Boeing or Aloha or the 737 or the U.S.A. Since the Aloha accident, unseen by the public, unprecedented improvements in maintenance have had to be made.

Far too many safety recommendations from the manufacturers were ignored by the airlines. The working groups have had the enormous task of reassessing all service instructions ever issued and deciding which must be made mandatory. Moreover they have rejected the previous belief that safety could be assured by inspection alone. If there is a safety hazard then a permanent fix must be found and applied.

Mandatory corrosion control programs have been developed and are being introduced from the start of 1992. These require that all operators have in place prevention and inspection systems sufficient to ensure that hazardous corrosion never occurs. If hazardous corrosion is ever found, it signifies that the operators whole program is suspect. It is no longer sufficient just to fix the immediate defect. The program must be reassessed and if necessary the whole fleet of aircraft must be re-inspected.

Another danger recognized by the working groups is that of repairs. Every aircraft suffers cracks, corrosion and occasional scrapes with service vehicles; and it all gets patched up. A hundred patches on an aircraft is not unusual. Too often they are riveted on in a hurry, with dubious engineering and dubious records. Every one has got to be found, inspected, evaluated and if necessary replaced. It is a huge task and will take years.

It should never have been necessary to make the extra work mandatory. It should have been good practice. Good practice fell by the wayside under the insidious pressures of complacency. Safety is no accident. It depends on the concerted effort of manufacturers, operators and regulators always working together to maintain the fine safety record of the aviation industry.

Nobody in our industry must ever become complacent.

This story was originally published in BASI Journal and is reproduced with authors permission. (Photos from the NTSB files)

| ?AvStop Online Magazine Contact Us Return To News |