|

|

| INSTRUMENT PROCEDURES HANDBOOK |

|

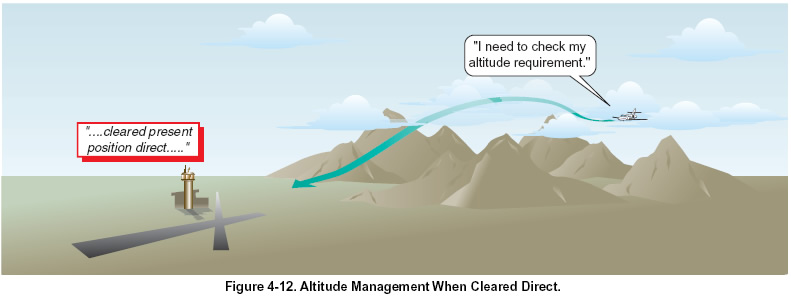

CONTROLLED FLIGHT INTO TERRAIN Inappropriate descent planning and execution during arrivals has been a contributing factor to many fatal aircraft accidents. Since the beginning of commercial jet operations, more than 9,000 people have died worldwide because of controlled flight into terrain (CFIT). CFIT is described as an event in which a normally functioning aircraft is inadvertently flown into the ground, water, or an obstacle. Of all CFIT accidents, 7.2 percent occurred during the descent phase of flight. The basic causes of CFIT accidents involve poor flight crew situational awareness. One definition of situational awareness is an accurate perception by pilots of the factors and conditions currently affecting the safe operation of the aircraft and the crew. The causes of CFIT are the flight crews’ lack of vertical position awareness or their lack of horizontal position awareness in relation to the ground, water, or an obstacle. More than two-thirds of all CFIT accidents are the result of an altitude error or lack of vertical situational awareness. CFIT accidents most often occur during reduced visibility associated with instrument meteorological conditions (IMC), darkness, or a combination of both. The inability of controllers and pilots to properly communicate has been a factor in many CFIT accidents. Heavy workloads can lead to hurried communication and the use of abbreviated or non-standard phraseology. The importance of good communication during the arrival phase of flight was made evident in a report by an air traffic controller and the flight crew of an MD-80. The controller reported that he was scanning his radarscope for traffic and noticed that the MD-80 was descending through 6,400 feet. He immediately instructed a climb to at least 6,500 feet. The pilot responded that he had been cleared to 5,000 feet and then climbed to… The pilot reported that he had “heard” a clearance to 5,000 feet and read back 5,000 feet to the controller and received no correction from the controller. After almost simultaneous ground proximity warning system (GPWS) and controller warnings, the pilot climbed and avoided the terrain. The recording of the radio transmissions confirmed that the airplane was cleared to 7,000 feet and the pilot mistakenly read back 5,000 feet then attempted to descend to 5,000 feet. The pilot stated in the report: “I don’t know how much clearance from the mountains we had, but it certainly makes clear the importance of good communications between the controller and pilot.” ATC is not always responsible for safe terrain clearance for the aircraft under its jurisdiction. Many times ATC will issue en route clearances for pilots to proceed off airway direct to a point. Pilots who accept this type of clearance also are accepting responsibility for maintaining safe terrain clearance. Know the height of the highest terrain and obstacles in the operating area. Know your position in relation to the surrounding high terrain. The following are excerpts from CFIT accidents related to descending on arrival: “…delayed the initiation of the descent…”; “Aircraft prematurely descended too early…”; “…late getting down…”; “During a descent…incorrectly cleared down…”; “…aircraft prematurely let down…”; “…lost situational awareness…”; “Premature descent clearance…”; “Prematurely descended…”; “Premature descent clearance while on vector…”; “During initial descent…” [Figure 4-12]

Practicing good communication skills is not limited to just pilots and controllers. In its findings from a 1974 air carrier accident, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) wrote, “…the extraneous conversation conducted by the flight crew during the descent was symptomatic of a lax atmosphere in the cockpit that continued throughout the approach.” The NTSB listed the probable cause as “…the flight crew’s lack of altitude awareness at critical points during the approach due to poor cockpit discipline in that the crew did not follow prescribed procedures.” In 1981, the FAA issued Parts 121.542 and 135.100, Flight Crewmember Duties, commonly referred to as “sterile cockpit rules.” The provisions in this rule can help pilots, operating under any regulations, to avoid altitude and course deviations during arrival. In part, it states: (a) No certificate holder shall require, nor may any flight crewmember perform, any duties during a critical phase of flight except those duties required for the safe operation of the aircraft. Duties such as company required calls made for such purposes as ordering galley supplies and confirming passenger connections, announcements made to passengers promoting the air carrier or pointing out sights of interest, and filling out company payroll and related records are not required for the safe operation of the aircraft. (b) No flight crewmember may engage in, nor may any pilot in command permit, any activity during a critical phase of flight that could distract any flight crewmember from the performance of his or her duties or which could interfere in any way with the proper conduct of those duties. Activities such as eating meals, engaging in nonessential conversations within the cockpit and nonessential communications between the cabin and cockpit crews, and reading publications not related to the proper conduct of the flight are not required for the safe operation of the aircraft. (c) For the purposes of this section, critical phases of flight include all ground operations involving taxi, takeoff and landing, and all other flight operations conducted below 10,000 feet, except cruise flight. |