|

|

| |

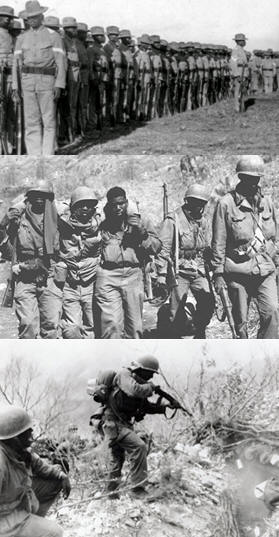

The 24th Infantry

In Japan

|

|

The 24th Infantry Regiment

was a unit of the United States Army that was

active from 1869 until 1951, and again from 1995

until 2006. The unit was primarily made up of

African-American soldiers. The 24th Infantry

Regiment is notable for serving their country

when systemic racism was overt, and when black

troops were treated as "second class" due to

segregation.

The 24th Infantry's service in the occupation of Japan was a model not

only of the tensions that dogged all-black units in that day but also of

the subtle interplay those problems could have with the many challenges

the Army faced in the postwar period. On the surface, conditions within

the unit seemed favorable. The regiment was well situated in its base at

Gifu, and life seemed good for its troops. Down below, however, there was

much that was wrong.

To begin with, the Army itself was undergoing extreme turbulence. Personnel

strengths gyrated up and down throughout the postwar period as budgets

and manpower policies changed with the political winds. Training declined,

equipment shortages grew, and officers who might have sought to make the

military a career left the service. Training improved in 1949 but still

remained inadequate.

The Eighth Army in

Japan provides a case in point. Most of its soldiers were civilians at heart,

intent upon enjoying the pleasures of life in occupied Japan, where a GI's

salary could pay for an abundance of readily available pleasures. In many units,

black-market activities thrived, alcoholism was rife, and venereal disease

flourished.

But the number one

transgression in the Eighth Army in the spring

of 1950 was drug abuse. It spread with sometimes

near abandon in many units, particularly those

that served like the 24th Infantry in or near

large port cities.

The 24th Infantry, for its part, experienced the same difficulties as

the rest of the Army, but it generally maintained high esprit de corps.

It gained a deserved reputation for its prowess at sports and its fine

marching. Its training was on a par with that of most other units, and at

the beginning of the Korean War it was one of a

few that had undergone some form of regimental

maneuvers. While the General Classification Test

scores for its men were significantly lower than

for the whites in other regiments, those figures

were inadequate as measures of innate

intelligence.

|

|

|

| |

|

Indeed, many white

officers assigned to the regiment would later

insist that the enlisted men and noncommissioned

officers of the unit, whatever their schooling,

often knew their jobs and did them well. Even so, the 24th remained a racially segregated regiment, and the effects

of that system ate incessantly into the bonds that held the unit together.

They were often hidden at Gifu, which had become an artificial island for

blacks-"our own little world," as some of the men described it-but

even there, discontent festered just beneath the surface calm. Unwritten

but firmly held assignment policies, for example, ensured that black officers,

whatever their competence, would rarely if ever command whites. Throughout

the years prior to the Korean War, as a result, except for one lieutenant

colonel, the senior commanders of the regiment were white. As for its field-grade

officers, only the chaplains and a few majors in unimportant assignments

were black. |

|

|

|

|

| |

The mistrust that

resulted on both sides was largely hidden behind a screen of

military conventions and good manners, but it was still there.

Black officers were frustrated and resentful. They saw that most

promotions and career-enhancing assignments went to white

officers, some of whom were clearly inferior to them in

education and military competence. Aware, as well, that few if

any of them would ever rise to a rank above captain, they could

only conclude that the Army considered them second class. They

retaliated by developing a view, as one African-American

lieutenant observed years later, that the 24th was a "penal"

regiment for white officers who had "screwed up." The whites,

for their part, although a number got along well with their

black colleagues, mainly kept to themselves.

The tensions that existed among the regiment's officers had

parallels in enlisted ranks. At times, black soldiers worked

well with their white superiors and relations between the races

were open, honest, and mutually fulfilling, primarily because

the white officers recognized the worth of their subordinates

and afforded them the impartiality and dignity they deserved.

Many whites, however, shared the racially prejudiced attitudes

and beliefs common to white civilian society. Although

infrequent, enough instances of genuine bigotry occurred to

cement the idea in the minds of black enlisted men that their

white officers were racially prejudiced.

As the regiment's stay lengthened at Gifu, an unevenness came

into being that subtly affected military readiness. In companies

commanded by white officers who treated their men with respect

but refused to accept low standards of discipline and

performance, racial prejudice tended to be insignificant, and a

bond, of sorts, developed between those who were leaders and

those who were led. In others, often commanded by officers who

failed to enforce high standards out of condescension, because

they wished to avoid charges of racial prejudice, or because

they were simply poor leaders, the bonds of mutual respect and

reliance were weak. On the surface, all seemed to run well

within those units. Underneath, however, hostility and

frustration lingered, to break forth only when the units faced

combat and their soldiers realized their lives depended on

officers they could not trust.

The problem might have had little effect on readiness if

officers had received the time to work out their relationships

with their men, but competition among them for Regular Army

commissions, under the so-called Competitive Tour Program,

produced a constant churning within the regiment. Officers

arrived at units, spent three months in a position, and then

departed for new assignments. In addition, the officer

complements of entire companies sometimes changed abruptly to

maintain segregation and to ensure that a black would never

command whites. Under the circumstances, officers often had

little time to think through what they were doing. Not only were

their own assignments temporary, the group of officers they

commanded was also in constant turmoil. A confluence of good

officers might, for a time, produce a cohesive, effective,

high-performing company, but everything might dissolve over

night with a change of command.

Under the circumstances, the personality of the regimental

commander was vital, and for much of the time in Japan the unit

was commanded by an officer who seemed ideally suited for the

job. Strong, aggressive, experienced, Colonel Michael E.

Halloran held the respect and support of most of his

subordinates, whether commissioned or enlisted. The performance

of the regiment while he was in charge was all that anyone could

have expected at that time and in that place. The effectiveness

of Halloran's successor is more in question. Colonel Horton V.

White was intelligent and well intentioned, but his low-key,

hands-off style of command did little to fill the void when

Halloran departed.

It would be interesting to determine what the results would have

been if the 24th had gone to war under Halloran rather than

White, but the efficiency of a unit in combat is rarely

determined by the presence of a single individual, however

experienced and inspiring. What is clear, is that if the 24th

went into battle much as the other regiments in the Eighth Army

did-poorly trained, badly equipped, and short on experience-it

carried baggage none of the others possessed, all the problems

of trust and lack of self-confidence that the system of

segregation had imposed. |

|

| |

©AvStop

Online Magazine

Contact

Us

Return To News

|

| |

|

|

|