|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||

|

Japanese War

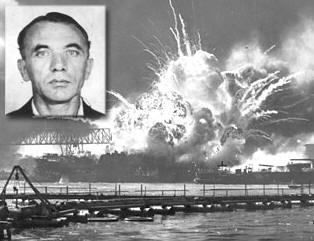

Fighters, Remembering Pearl Harbor Seventy Years Ago Today By Daniel Baxter |

||||

|

December 7, 2011 - Seventy years ago today on December

7, 1941, a sneak attack on Pearl Harbor took the lives

of more than 2,400 Americans, stunning the nation and

catapulting it into war. For the FBI, the attack and the

onset of war opened a new chapter in national security.

Even as Japanese bombs rained down, FBI Special Agent in Charge Robert Shivers in Honolulu was patched through via telephone to Director J. Edgar Hoover, who immediately put the Bureau on a 24/7 wartime footing according to its already well-made plans. In the days and months that followed, the FBI diligently and successfully worked to protect the American homeland from spies and saboteurs, building important new capabilities along the way. |

|||

|

On December 7, 1941, as bombs fell on American battleships at Pearl Harbor, Robert L. Shivers, Special Agent in Charge of the FBI's Honolulu office, was on the phone. Headquarters relayed his anxious call to New York, where Director Hoover was visiting. "The Japanese are bombing Pearl Harbor. It's war," Shivers said. "You may be able to hear it yourself. Listen!

Director

Hoover immediately flew back to Washington, mindful of the plans

that his agency had made for this eventuality. Some 2,400 brave

U.S. sailors had already died in the early hours of that fateful

Sunday. The attack was a surprise; that Japan was readying war

against America was not. Contingency plans had been made

throughout the U.S. government, and they were immediately

implemented to ensure American security in the weeks, months,

and years after the surprise attack.

And what

about FBI plans? What had the Bureau set in place in the event

of war? It had made the investigation of sabotage, espionage,

and subversion a top priority and agents made surveys of

industrial plants that were vital to American security in order

to prevent sabotage and espionage. It had expanded its

intelligence programs, including undercover work in South and

Central America to identify Nazi spies.

The FBI had performed and continued to perform exhaustive background checks on federal workers, to keep enemy agents from infiltrating the government. It had been directed to draw up plans for a voluntary board, turned over to and headed by a newspaperman, to review media stories in order to prevent information from being released that might harm American troops. Mindful of free speech protections, this independent board operated with the voluntary cooperation of the media. |

||||

|

It had expanded the number of professionally trained police through its National Academy program to aid the Bureau in times of crisis. This cadre of professionals effectively forestalled well-meaning but overzealous civilian plans to "help" law enforcement with vigilantism. The FBI had learned a lesson from World War I when groups like the American Protective League abused the civil rights of Americans in its efforts to identify German spies, draft resisters, and other threats. And it had identified German, Italian, and Japanese aliens who posed a clear threat to the United States in the event of war so that when President Roosevelt ordered it?and he did, on the evening of December 7?the Bureau could immediately arrest these enemies and present them to immigration for hearings (represented by counsel) and possible deportation. A few?like Bernard Julius Otto Kuehn, the German national involved in signaling the Japanese invasion fleet headed for Pearl Harbor?were arrested and prosecuted for espionage and other crimes against the U.S. Now, on December 7, it immediately implemented a 24/7 schedule at Headquarters and in its field operations.

For his part, Shivers who had already made progress in sorting out the FBI's division of intelligence and security responsibilities with the Navy?immediately placed the Japanese Consulate under police guard, both to protect the diplomats from retaliation and to prevent their escape. His agents seized a large quantity of suspiciously coded documents that consulate employees tried to hastily burn and began running down key cases of espionage (especially that of Otto Kuehn).

Kuehn a member of

the Nazi party had arrived in Hawaii in 1935. By 1939, the Bureau was

suspicious of him. He had questionable contacts with the Germans and

Japanese. He'd lavishly entertained U.S. military officials and

expressed interest in their work. He had two houses in Hawaii, lots of

dough, but no real job. Investigations by the Bureau and the Army,

though, never turned up definite proof of his spying. Not until the fateful attack of December 7, 1941. Honolulu Special Agent in Charge Robert Shivers immediately began coordinating homeland security in Hawaii and tasked local police with guarding the Japanese consulate. They found its officials trying to burn reams of paper. These documents once decoded?included a set of signals for U.S. fleet movements. |

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| blog comments powered by Disqus | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| ?AvStop

Online Magazine

Contact

Us

Return To News

|

||||||||

|