|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

||||

|

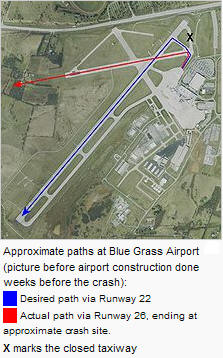

On August 27,

2006, about 0606:35 eastern daylight time, Comair flight 5191, a

Bombardier CL-600-2B19, N431CA, crashed during takeoff from Blue Grass

Airport, Lexington, Kentucky. The flight crew was instructed to take off

from runway 22 but instead lined up the airplane on runway 26 and began

the takeoff roll. The airplane ran off the end of the runway and

impacted the airport perimeter fence, trees, and terrain.

The captain,

flight attendant, and 47 passengers were killed, and the first officer

received serious injuries. The airplane was destroyed by impact forces

and postcrash fire. The flight was operating under the provisions of 14

Code of Federal Regulations Part 121 and was en route to

According to a

customer service agent working in the Comair operations area, the flight

crew checked in for the flight at 0515. The agent indicated that the

crewmembers were casually conversing and were not yawning or rubbing

their eyes.

The flight crew

collected the flight release paperwork, which included weather

information, safety-of-flight notices to airmen (NOTAM), the tail number

of the airplane to be used for the flight, and the flight plan. The

flight crew then proceeded to an area on the air carrier ramp where two

Comair Canadair regional jet (CRJ) airplanes were parked.

|

|||

|

||||

|

The cockpit voice

recorder (CVR) recording began about 0536:08. At that time, the flight

crew was conducting standard preflight preparations. About 0548:24, the

CVR recorded automatic terminal information service (ATIS) information

"alpha," which indicated that runway 22 was in use. About 1 minute

afterward, the first officer told the controller that he had received

the ATIS information.

About 0549:49, the

controller stated, "cleared to

The first officer

replied, "okay, got uh,

About 0552:04, the

captain began a discussion with the first officer about which of them

should be the flying pilot to ATL. The captain offered the flight to the

first officer, and the first officer accepted. About 0556:14, the

captain stated, "Comair standard," which is part of the taxi briefing,

and "run the checklist at your leisure."

About 0556:34, the

first officer began the takeoff briefing, which is part of the before

starting engines checklist. During the briefing, he stated, "he said

what runway ... two four," to which the captain replied, "it's two two."

The first officer

continued the takeoff briefing, which included three additional

references to runway 22. After briefing that the runway end identifier

lights were out, the first officer commented, "came in the other night

it was like ... lights are out all over the place." The first officer

also stated, "let's take it out and ... take ... [taxiway] Alpha. Two

two's a short taxi." The captain called the takeoff briefing complete

about 0557:40.

Starting about

0558:15, the first officer called for the first two items on the before

starting engines checklist. When the captain pointed out that the before

starting engines checklist had already been completed, the first officer

questioned, "we did"? Afterward, the first officer briefed the takeoff

decision speed (V1) as 137 knots and the rotation speed (VR) as 142

knots.

Flight data

recorder (FDR) data for the accident flight started about 0558:50. The

FDR showed that, at some point before the start of the accident flight

recording, the pilots' heading bugs had been set to 227º, which

corresponded to the magnetic heading for runway 22.

About 0559:14, the

captain stated that the airplane was ready to push back from the gate.

FDR data showed that, about 0600:08 and 0600:55, the left and right

engines, respectively, were started.

About 0602:01, the

first officer notified the controller that the airplane was ready to

taxi. The controller then instructed the flight crew to taxi the

airplane to runway 22. This instruction authorized the airplane to cross

runway 26 (the intersecting runway) without stopping. The first officer

responded, "taxi two two." FDR data showed that the captain began to

taxi the airplane about 0602:17. About the same time, SkyWest flight

6819 departed from runway 22.

About 0602:19, the

captain called for the taxi checklist. Beginning about 0603:02, the

first officer made two consecutive statements, "radar terrain displays"

and "taxi check's complete," that were spoken in a yawning voice. About

0603:38, American Eagle flight 882 departed from runway 22.

From about 0603:16

to about 0603:56, the flight crew engaged in conversation that was not

pertinent to the operation of the flight. About 0604:01, the first

officer began the before takeoff checklist and indicated again that the

flight would be departing from runway 22.

FDR data showed

that, about 0604:33, the captain stopped the airplane at the holding

position, commonly referred to as the hold short line, for runway 26.

Afterward, the first officer made an announcement over the public

address system to welcome the passengers and completed the before

takeoff checklist. About 0605:15, while the airplane was still at the

hold short line for runway 26, the first officer told the controller

that "Comair one twenty one" was ready to depart at his leisure; about 3

seconds later, the controller responded, "Comair one ninety one ... fly

runway heading. Cleared for takeoff." Neither the first officer nor the

controller stated the runway number during the request and clearance for

takeoff. FDR data showed that, about 0605:24, the captain began to taxi

the airplane across the runway 26 hold short line. The CVR recording

showed that the captain called for the lineup checklist at the same

time.

About 0605:40, the

controller transferred responsibility for American Eagle flight 882 to

the Indianapolis Air Route Traffic Control Center (ARTCC). FDR data

showed that, about 1 second later, Comair flight 5191 began turning onto

runway 26. About 0605:46, the first officer called the lineup checklist

complete.

About 0605:58, the

captain told the first officer, "all yours," and the first officer

acknowledged, "my brakes, my controls." FDR data showed that the

magnetic heading of the airplane at that time was about 266º, which

corresponded to the magnetic heading for runway 26. About 0606:05, the

CVR recorded a sound similar to an increase in engine rpm. Afterward,

the first officer stated, "set thrust please," to which the captain

responded, "thrust set." About 0606:16, the first officer stated,

"[that] is weird with no lights," and the captain responded, "yeah," 2

seconds later.

About 0606:24, the

captain called "one hundred knots," to which the first officer replied,

"checks." At 0606:31.2, the captain called, "V one, rotate," and stated,

"whoa," at 0606:31.8. FDR data showed that the callout for V1 occurred 6

knots early and that the callout for VR occurred 11 knots early; both

callouts took place when the airplane was at an airspeed of 131 knots.

FDR data also showed that the control columns reached their full aft

position about 0606:32 and that the airplane rotated at a rate of about

10º per second.

The airplane

impacted an earthen berm located about 265 feet from the end of runway

26, and the CVR recorded the sound of impact at 0606:33.0. FDR airspeed

and altitude data showed that the airplane became temporarily airborne

after impacting the berm but climbed less than 20 feet off the ground.

The CVR recorded

an unintelligible exclamation by a flight crewmember at 0606:33.3. FDR

data showed that the airplane reached its maximum airspeed of 137 knots

about 0606:35. The aircraft performance study for this accident showed

that, at that time, the airplane impacted a tree located about 900 feet

from the end of runway 26. The CVR recorded an unintelligible

exclamation by the captain at 0606:35.7, and the recording ended at

0606:36.2.

In a postaccident

interview, the controller stated that he did not see the airplane take

off. The controller also stated that, after hearing a sound, he saw a

fire west of the airport and activated the crash phone (the direct

communication to the airport's operations center and fire station) in

response.

The air traffic

control (ATC) transcript showed that the crash phone was activated about

0607:17 and that the airport operations center dispatcher responded to

the crash phone about 0607:22. According to the ATC transcript, the

controller announced an "alert three" and indicated that a Comair jet

taking off from runway 22 was located at the west side of the airport

just off the approach end of runway 8 (which is also the departure end

of runway 26). Section 1.15.1 discusses the emergency response.

Findings

1) The captain and

the first officer were properly certificated and qualified under Federal

regulations. There was no evidence of any medical or behavioral

conditions that might have adversely affected their performance during

the accident flight. Before reporting for the accident flight, the

flight crewmembers had rest periods that were longer than those required

by Federal regulations and company policy.

2) The accident

airplane was properly certified, equipped, and maintained in accordance

with Federal regulations. The recovered components showed no evidence of

any structural, engine, or system failures.

3) Weather was not

a factor in this accident. No restrictions to visibility occurred during

the airplane's taxi to the runway and the attempted takeoff. The taxi

and the attempted takeoff occurred about 1 hour before sunrise during

night visual meteorological conditions and with no illumination from the

moon.

4) The captain and

the first officer believed that the airplane was on runway 22 when they

taxied onto runway 26 and initiated the takeoff roll.

5) The flight crew

recognized that something was wrong with the takeoff beyond the point

from which the airplane could be stopped on the remaining available

runway.

6) Because the

accident airplane had taxied onto and taken off from runway 26 without a

clearance to do so, this accident was a runway incursion.

7) Adequate cues

existed on the airport surface and available resources were present in

the cockpit to allow the flight crew to successfully navigate from the

air carrier ramp to the runway 22 threshold.

8) The flight

crewmembers' nonpertinent conversation during the taxi, which was not in

compliance with Federal regulations and company policy, likely

contributed to their loss of positional awareness.

9) The flight

crewmembers failed to recognize that they were initiating a takeoff on

the wrong runway because they did not cross-check and confirm the

airplane's position on the runway before takeoff and they were likely

influenced by confirmation bias.

10) Even though

the flight crewmembers made some errors during their preflight

activities and the taxi to the runway, there was insufficient evidence

to determine whether fatigue affected their performance.

11) The flight

crew's noncompliance with standard operating procedures, including the

captain's abbreviated taxi briefing and both pilots' nonpertinent

conversation, most likely created an atmosphere in the cockpit that

enabled the crew's errors.

12) The controller

did not notice that the flight crew had stopped the airplane short of

the wrong runway because he did not anticipate any problems with the

airplane's taxi to the correct runway and thus was paying more attention

to his radar responsibilities than his tower responsibilities.

13) The controller

did not detect the flight crew's attempt to take off on the wrong runway

because, instead of monitoring the airplane's departure, he performed a

lower-priority administrative task that could have waited until he

transferred responsibility for the airplane to the next air traffic

control facility.

14) The controller

was most likely fatigued at the time of the accident, but the extent

that fatigue affected his decision not to monitor the airplane's

departure could not be determined in part because his routine practices

did not consistently include the monitoring of takeoffs.

15) The Federal

Aviation Administration's operational policies and procedures at the

time of the accident were deficient because they did not promote optimal

controller monitoring of aircraft surface operations.

16) The first

officer's survival was directly attributable to the prompt arrival of

the first responders; their ability to extricate him from the cockpit

wreckage; and his rapid transport to the hospital, where he received

immediate treatment.

17) The emergency

response for this accident was timely and well coordinated.

18) A standard

procedure requiring 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 91K, 121, and

135 pilots to confirm and cross-check that their airplane is positioned

at the correct runway before crossing the hold short line and initiating

a takeoff would help to improve the pilots' positional awareness during

surface operations.

19) The

implementation of cockpit moving map displays or cockpit runway alerting

systems on air carrier aircraft would enhance flight safety by providing

pilots with improved positional awareness during surface navigation.

20) Enhanced

taxiway centerline markings and surface painted holding position signs

provide pilots with additional awareness about the runway and taxiway

environment.

21) This accident

demonstrates that 14 Code of Federal Regulations 91.129(i) might result

in mistakes that have catastrophic consequences because the regulation

allows an airplane to cross a runway during taxi without a pilot request

for a specific clearance to do so.

22) If controllers

were required to delay a takeoff clearance until confirming that an

airplane has crossed all intersecting runways to a departure runway, the

increased monitoring of the flight crew's surface navigation would

reduce the likelihood of wrong runway takeoff events.

23) If controllers

were to focus on monitoring tasks instead of administrative tasks when

aircraft are in the controller's area of operations, the additional

monitoring would increase the probability of detecting flight crew

errors.

24) Even though

the air traffic manager's decision to staff midnight shifts at Blue

Grass Airport with one controller was contrary to Federal Aviation

Administration verbal guidance indicating that two controllers were

needed, it cannot be determined if this decision contributed to the

circumstances of this accident.

25) Because of an

ongoing construction project at Blue Grass Airport, the taxiway

identifiers represented in the airport chart available to the flight

crew were inaccurate, and the information contained in a local notice to

airmen about the closure of taxiway A was not made available to the crew

via automatic terminal information service broadcast or the flight

release paperwork.

26) The

controller's failure to ensure that the flight crew was aware of the

altered taxiway A configuration was likely not a factor in the crew's

inability to navigate to the correct runway. 27) Because the information in the local notice to airmen (NOTAM) about the altered taxiway A configuration was not needed for the pilots' wayfinding task, the absence of the local NOTAM from the flight release paperwork was not a factor in this accident. 28) The presence of the extended taxiway centerline to taxiway A north of runway 8/26 was not a factor in this accident. |

|

|

| Other News Stories |

| ©AvStop

Online Magazine

Contact

Us

Return To News

|

|