|

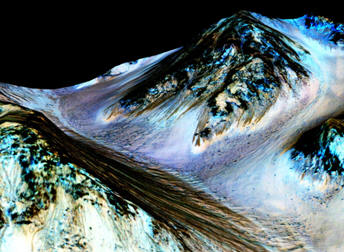

Ojha first noticed these puzzling features as a

University

of Arizona

undergraduate student in 2010, using images from the

MRO's High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE).

HiRISE observations now have documented RSL at dozens of

sites on Mars. The new study pairs HiRISE observations

with mineral mapping by MRO’s Compact Reconnaissance

Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM). The

spectrometer observations show signatures of hydrated

salts at multiple RSL locations, but only when the dark

features were relatively wide. When the researchers

looked at the same locations and RSL weren't as

extensive, they detected no hydrated salt.

Ojha and his co-authors interpret the spectral

signatures as caused by hydrated minerals called

perchlorates. The hydrated salts most consistent with

the chemical signatures are likely a mixture of

magnesium perchlorate, magnesium chlorate and sodium

perchlorate. Some perchlorates have been shown to keep

liquids from freezing even when conditions are as cold

as minus 94 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 70 Celsius). On

Earth, naturally produced perchlorates are concentrated

in deserts, and some types of perchlorates can be used

as rocket propellant.

Perchlorates have previously been seen on Mars. NASA's

Phoenix

lander and Curiosity rover both found them in the

planet's soil, and some scientists believe that the

Viking missions in the 1970s measured signatures of

these salts. However, this study of RSL detected

perchlorates, now in hydrated form, in different areas

than those explored by the landers. This also is the

first time perchlorates have been identified from orbit.

MRO has been examining Mars since 2006 with its six

science instruments. "The ability of MRO to

observe for multiple Mars years with a payload able to

see the fine detail of these features has enabled

findings such as these: first identifying the puzzling

seasonal streaks and now making a big step towards

explaining what they are," said Rich Zurek, MRO project

scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in

Pasadena, California.

For Ojha, the new findings are more proof that the

mysterious lines he first saw darkening Martian slopes

five years ago are, indeed, present-day water. "When

most people talk about water on Mars, they're usually

talking about ancient water or frozen water," he said.

"Now we know there’s more to the story. This is the

first spectral detection that unambiguously supports our

liquid water-formation hypotheses for RSL."

The discovery is the latest of many breakthroughs by

NASA’s Mars missions. “It took multiple spacecraft over

several years to solve this mystery, and now we know

there is liquid water on the surface of this cold,

desert planet,” said Michael Meyer, lead scientist for

NASA’s Mars Exploration Program at the agency’s

headquarters in Washington. “It seems that the more we study

Mars, the more we learn how life could be supported and

where there are resources to support life in the

future.”

|